A History of the Vikings

Chapter 3

99

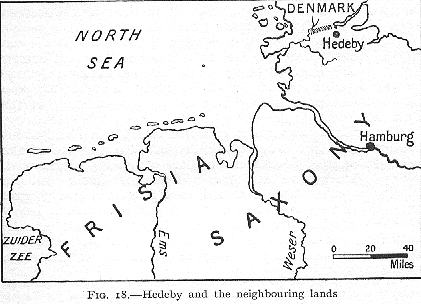

'30s is not known, for who exactly this newcomer was Adam of Bremen does not say. But he was evidently not a Dane since he arrived 'from Nordmannia'. and the natural conclusion is that he was a Norwegian, or, just conceivably, another Swede. 1 Thus it is probable that Hedeby under Hardegon and his house was still a foreign settlement outside of the Danish dominion, and so, indeed, it continued to be even after the next change in the ruling dynasty, which took place in the '8os of the tenth

1. There has been considerable argument as to his identity and nationality. Formerly his name was assumed to be Hardecnut and he was believed to be either the father of the Danish king Gorm (who is known to have been so called) or Gorm himself. Everything depends, of course, upon the interpretation of the name of his country Nordmannia, for this might be translated Normandy, and therefore it is not impossible that Hardegon was a Dane returned from the colony overseas; but the fact remains that according to chronicle-usage Norway is much more likely to be the correct translation. It is worth noting, however, that Adam of Bremen uses the name Nordmannia in one instance as though it applied also to eastern Scandinavia, that is Sweden. For Hardegon's identity see L. Jacobsen, Svenskevaeldets Fald, Copenhagen, 1929, and the reviews of this notable book, e.g., S. Lindqvist, Namn och Bygd, 1929, p. 1, and V. La Cour, Hist. Tidsskrift, Copenhagen, 9 R. VI, 3, p. 459.

100

had become a powerful state and the foreigners' hold on the border-town was not destined to endure much longer. The end came about A.D. 995, when the Swedes were driven out by the Danish king, Svein Forkbeard, and the once busy mart was utterly destroyed.

The story of Denmark's development into the formidable kingdom ruled by Svein begins in the days of his grandfather Gorm, a monarch whose achievements history has unhappily failed to chronicle although his reputation as a mighty man has survived into saga-tradition. He was the last of the heathen kings of Denmark and reigned about the years A.D. 930-940, having his court at Jellinge in Jutland. Here it was that Gorm was laid to rest beneath a great barrow that can still be seen, and here too stands the gravemound, or cenotaph, (1) of Thyra, his queen, a royal lady who has been honoured in later days as a noble defender of the Danevirke. (2)

The great royal mounds of Gorm and Thyra stand about 200 feet apart and between the two is a stone carved at the order of Gorm's son Harald. It is richly ornamented, bearing on one face a figure of Christ and on another face an animal, each framed in an elaborate twisted loop of rope-pattern and enmeshed in heavy interlacing ribbons and twisting tendrils; on the third face, and continuing along the bottom of the other two

1. On the subject of the Jellinge barrows, see S. Lindqvist, Fornvännen, 1928, p. 257.

2. A stone stands at Jellinge bearing a Runic inscription that until recently was interpreted Gorm, the king, made this memorial for Thyra, his wife, Denmark's protector, and it was believed to prove that Thyra had directed and inspired her countrymen on some occasion when the safety of their land was threatened. The expression DanmarkaR bót has been the subject of much argument, but it is now held that this epithet does not justify Thyra's latter-day fame since it may well apply not to Thyra but to Gorm, the inscription then reading Gorm the king, Denmark's benefactor, made this memorial to Thyra, his wife. See Hans Brix , Acta Phil. Scand., II ( 1927), p. 110; and cf. H. Lis Jacobsen Brix and N. Möller, Gorm Konge og Thyra, Runernes Magt, Copenhagen, 1927; but note that Finnur Jónsson has opposed this new reading. The stone in question is now in the churchyard at Jellinge and there is considerable doubt as to its original position. Possibly it was not connected with Thyra's grave-mound but was erected during her lifetime by her husband, for Saxo ( I, 486) and the sagas (e.g. Fornmanna sögur, I, 119) say plainly that Thyra outlived Gorm. On the other hand, it is known that there was once a stone on the top of Thyra's mound; for the Jellinge stones, see L. Wimmer, Danske Runemindesmaerher, I, 2, pp. 8, 17, and cf. an important essay by Lauritz Weibull, Nordens hist. o. åy 1000, Lund, 1911, p. 1 ff.

Plate VI

Plate IV

(Opens New Window)

Memorial Stones Erected by King Gorm and King Harald Gormsson (Two Views) at Jellinge Denmark. Heights, 8 feet 3 inches and 4.5 feet

101

faces, is a Runic inscription that reads, 'Harald the king set up this memorial to Gorm, his father, and Thyra, his mother; that Harald who won for himself all Denmark and Norway and who made the Danes Christian.'

These are the words of a great king and, indeed, it is to Harald Gormsson, or Bluetooth (blátönn) as he is often called, that must be ascribed the honour of founding the Danish kingdom as a united and enduring whole. Tradition, from the saga-period onwards, has given Gorm the credit of this achievement, but the inscription on the Jellinge stone proves that Harald deemed himself in some special sense the founder of the Danish kingdom, perhaps by the consolidation of his father's territorial gains and the firm administration of newly acquired lands in Norway. His kingdom consisted of the Danish islands and Jutland as far south as the Danevirke, of Scania, and perhaps of a part of the Halland coast of Sweden, and of the Ranrike province and the Vik district of Norway. His boast that he counted this country also as a part of his realm was not merely a fiction of Danish imagination, even though it is certain that he never conquered nor controlled the whole of Norway; but he most assuredly became a dominating personality in Norwegian affairs. His influence here dates back to the time when the widow of Eric Bloodaxe, Gunnhild, and her sons were fighting against Haakon Æthelstan's-fosterson for the possession of Harald Fairhair's throne, for Harald Gormsson was Gunnhild's brother, and in return for the aid he lent her he became lord of the Ranrike on the east side of the Vik. Subsequently there was hostility between Gunnhild's sons and their too powerful uncle, so that Harald took the side of the usurper Jarl Haakon, who eventually overthrew them, and thereby increased his authority in Norway. Haakon was, in fact, his liegeman and was summoned to assist Harald when Otto ii attacked the southern boundaries of Denmark; henceforth all the Vik lands were under the direct control of the Danish king and they were no doubt included in the missionary activities that were a sequel to Harald's conversion to the Christian faith. Haakon's loyalty weakened as the years passed and there seems to have been war between him and Harald, a clash between newly Christian Denmark and still heathen Norway, but the Danish yoke was never completely thrown off and Harald Gormsson died master of the Vik.

The political success of the Danish king in his own realm is inseparably connected with his conversion to Christianity, an event that is described by the tenth-century monk Widukind

102

of Corvey in his chronicle. (1) During a feast at which the king was present there arose, Widukind relates, a dispute about the worship of the gods. The Danes conceded that Christ was veritably a god, but they avowed that the old gods were stronger than Christ because they revealed themselves to mortals with more powerful tokens and wonders. Thereupon Bishop Poppo testified that the Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost were one God, and that there was no other god, the so-called gods of the heathen being only demons. Harald asked if Poppo would prove his faith by ordeal and without hesitation Poppo replied that he would willingly do so. On the next day the king commanded a heavy piece of iron to be made red-hot and bade Poppo hold this as an evidence of his faith. This Poppo did for as long as the king desired, and when he was allowed to loose his hold of it he displayed for all to see hands that were unscathed by the hot metal. Thereupon the king said that he would honour Christ alone as the true God, and he commanded that the people over whom he ruled should abandon the heathen gods and worship the Christ.

The historicity of this picturesque story is negligible, but as to the main fact of Harald's conversion there can be no dispute. Equally certain is it that he did attempt to impose Christianity upon his dominions, even though it might be questioned if he was as successful in this attempt as the boast on the Jellinge stone pretends. It is possible that a wise foreign policy (2) led him to take this step, for there can have been no surer method of winning the lasting favour and support of the German emperor than by professing the Christian faith. Thus it may well be that Harald's major claims to greatness, the winning of a united Denmark and the conversion of the Danes to Christianity, ought to be considered as two noble achievements inspired by a single dominating purpose, namely the desire to rule a kingdom that could rank among the civilized states of Europe. Nevertheless, in this aim, if such an ambition really

1. III, 65 ( Pertz, M. G. H., SS. III, p. 462).

2. There is a truly remarkable letter ( Pertz, Mon. Germ. Hist., Dip. regum I, 294) purporting to have been written by Otto the Great in 965, the supposed year of Harald's baptism, in which the emperor promised that any lands in the mark or kingdom of the Danes at that time owned, or subsequently acquired, by the bishoprics of Sleswig, Ribe, and Aarhus, should be held free of all taxes and duties payable to Otto; furthermore he enjoined that the dependents and tenants on these lands should be responsible to no master other than the bishop. But this letter is probably an invention of the sixteenth century, see Hauck, Kirchengeschichte Deutschlands, III, p. 102; and J. Steenstrup, Danmarks Sydgraense, p. 54.

103

inspired him, he must be judged to have failed, for the time and the conditions within his realm were against him.

Although his relations with Otto the Great seem to have been for the most part amicable, it is said that immediately before the emperor's death Harald was under suspicion of plotting some mischief against the Germans, (1) and in 974, when the old emperor was dead and while Otto II was concerning himself with Bavarian politics, the Danes began to ravage the country beyond the Elbe. It is not unlikely that their raids were instigated by Harald, for it is possible that the Danish king believed that a favourable opportunity had arrived to increase his kingdom and to rid it of a now oppressive German yoke. (2) Otto's anger was aroused and he collected an army. Driving back the invading Danes, he marched upon Denmark to exact reprisals, although Harald at once attempted to stop him with bribes and entreaties for peace. At length Otto reached the Danevirke, where he found that Harald had barred his further progress by an army of Norwegians under Haakon. An indecisive action was fought, but the Norwegians, who had got the better of the fight and had no wish to take part in a protracted winter campaign, boasted themselves the victors and soon afterwards returned to their own land. Meanwhile Otto directed a new attack on the Danevirke at a point in the fortifications where there was a gap called Wieglesdor, and he succeeded in breaking through. Harald thereupon sued for peace, which was granted upon the condition of his paying a heavy tribute. Before his return Otto built a fortress on the frontier, a place that has been doubtfully identified as a camp in the line of the Danevirke close to the Danevirke lake. The whole campaign lasted about three months and took place in the early winter. (3)

Harald died about A.D. 986, the single lord of all Denmark, and with his reign the goal of the present chapter, so far as his country is concerned, has been reached. The formation of the Swedish state in the dark years following upon the battle of Bravalla in the eighth century has already been recounted and the time has come, therefore, to tell the genesis of the kingdom

1. Pertz, Mon. Germ. Hist., SS. XX, 787.

2. The chronicler calls him incentor malorum and describes him as having himself taken part in the raids ( Pertz, Mon. Germ. Hist., SS. XX, 788).

3. The accounts are conflicting and the details hard to follow. There is an excellent study of the campaign by Henrik Ussing, Festkrift til Finnur Jónsson, Copenhagen, 1928, p. 140; this should be compared with K. Uhlirz, Otto II and Otto III, Jahrb. des deutschen Geschichte, Leipsig, 1902, pp. 55, 56.

<< Previous Page Next Page >>

© 2004-2007 Northvegr.

Most of the material on this site is in the public domain. However, many people have worked very hard to bring these texts to you so if you do use the work, we would appreciate it if you could give credit to both the Northvegr site and to the individuals who worked to bring you these texts. A small number of texts are copyrighted and cannot be used without the author's permission. Any text that is copyrighted will have a clear notation of such on the main index page for that text. Inquiries can be sent to info@northvegr.org. Northvegr™ and the Northvegr symbol are trademarks and service marks of the Northvegr Foundation.

|