Chapter 3

93

In the 30's and 40's of the ninth century, Horik, another of Godfred's sons, is named as Danish king, a personage who is also mentioned in the life of Anskar, the missionary, and plays a not inconsiderable part in Frankish politics of this period (p. 195). It is said of Horik that, although at one period he was sole king of Denmark, in 850 he was forced to concede two portions of his kingdom to relatives who had attacked him, and that four years later all three kings fell in a war with Horik's nephew Guthorm. The crown then passed to relatives of Harald, but in 857 a second Horik is named as king. At the same time, however, a part of the realm was possessed by another king called Rorik who plays a famous part in viking history and who was Harald's brother. Much later, in 873, there is further mention of two Danish kings, Sigfred and Halfdan, (1) ruling simultaneously, each of them making peace with the Frankish emperor Louis the German.

It seems plain that throughout this period there can have been no such thing as a single and undivided kingdom of Denmark, except perhaps for short lengths of time when some powerful chieftain won for himself a temporary supremacy. But, for the most part, the country's history is one of a turmoil of warring princes who struggled continuously for the possession of increased dominions at their neighbour's expense, sometimes courting the favour of the Franks or sometimes standing forth in armed revolt against them. (2)

This reading of the state of affairs in ninth-century Denmark can in a small measure be confirmed by appeal to another source of information, namely two travellers' accounts of Scandinavia. Shortly before the year 900 the English king Alfred the Great made a translation of a history of the world written five hundred years earlier by Orosius, and to this he added some general information about Europe and also the narratives of journeys made in northern Europe by two men, Ottar (Ohthere) and Wulfstan. In his own remarks upon the northern countries Alfred distinguishes between the South Danes living in a land having the North Sea on the west and the Baltic on the east (i.e. Jutland, and presumably central Jutland in view of his further remarks) and

1. They were perhaps sons of Ragnar Lodbrok (pp. 203, 231) and probably of the house of Harald.

2. On this difficult subject of the ninth-century Danish kings, see W. Vogel, Die Normannen, Heidelberg, 1906, p. 57 ff., p. 403 ff., and Jan de Vries, De Wikingen in de lage landen bij de Zee, Haarlem, 1923, esp. Ch. V and appendix 1, p. 351.

94

the North Danes who lived to the east and north of them, both on the Continent (this must mean north Jutland and not Scania) and on islands (Zealand and the Danish archipelago). (1)

Ottar, the first of the two travellers, was a northern trader from Halogaland in Norway. He said that to the south of his country at a distance of a month's sail, always with a fair wind and riding at anchor each night, was a port Sciringes-heal (Skiringssal), now known to have been situated near Tjölling at the mouth of the Oslo fjord. From that port a sail of five days took one to Haethan (Hedeby), near the modern Sleswig, and this town, he said, belonged to the Danes. For the first three days of the journey there was open sea to starboard and ' Denmark' on the port side, but for the last two days Jutland and Sillande (south Jutland) and many islands lay to starboard. To port now were islands (Zealand and others) that belonged to Denmark. (2)

Hedeby was the point of departure for Wulfstan, the second traveller. He went to Truso at the mouth of the Weichsel, taking seven days and nights on the journey. Wendland in north-east Germany was on his starboard side, and to port were Langeland, Laaland, Falster, and Scania, all of which belonged to Denmark. Then he came to Bornholm, an island having a king of its own, and after that he left on the port side Blekinge, M÷re, Öland, and Gotland, tracts of the Scandinavian mainland and two large islands that all belonged to Sweden.

These accounts, in conjunction with Alfred's own observations, are sufficient to show that there was as yet no single kingdom of Denmark and that the Danes were divided into two states, the one occupying the greater part of Jutland, and the other comprising Zealand and the islands, the Scania district of southern Sweden, and, perhaps, some territory in north Jutland. At the end of the ninth century, then, Denmark had not achieved the political solidarity already won by the Swedish state, and another century must run more than half its course before the Danes can be counted as a nation united under one rule.

1. Alfred Orosius, ed. H. Sweet, Early English Text Soc., 1883, p. 16.

2. As proof that the coastal tracts of Sweden and the country up to and including Vestfold in Norway were under Danish control in the ninth century, the Einhardi Annales (Pertz, Mon. Germ. Hist. SS. I, 200) are often quoted, e.g. Camb. Med. Hist., III, 313 . But I am not sure that in the passage concerned Westarfolda, the extreme district of the realm of the joint Danish kings Harald and Ragnfröd, is really Vestfold in Norway. The context suggests that a district in Jutland is more likely.

95

96

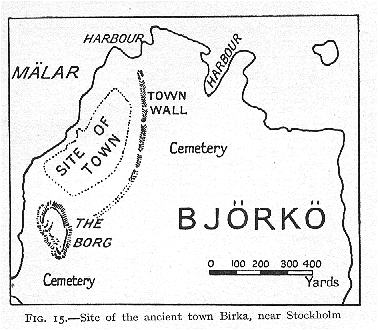

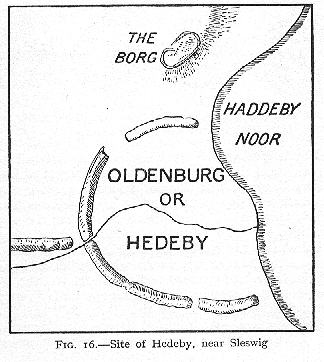

The late ninth and early tenth centuries, however, witnessed one very important event in the economic history of the North, and that was the rise to fame of notable and busy ports at Birka in Sweden and Hedeby in Denmark. Birka (Latin form of Björkö) was situated on the little Björkö island on the Mälar lake west of Stockholm, and was, at the time when it was visited by the missionary Anskar, a seat of the Swedish king. The town lay within a fortified area of some nineteen acres and seems to have been occupied from the ninth century until about 1050. Hedeby stood, as has been said, on the coast of Haddeby Nor in Sleswig, outside Godfred's Danevirke and in territory that had been left sparsely populated by the migration of the Angles; it was

defended by a semicircular dyke enclosing an area of 54 acres. The excavation of the place yielded a rich harvest of finds, now in the Kiel Museum, that suggest an occupation lasting from the late ninth century to the middle of the eleventh century.

The most probable of the theories concerning the origin and interconnexion of the two towns is that both of them were first and foremost market-places established as a result of the enterprise of the Frisian merchants who traded so busily with the north in the ninth century and who bartered the weapons, glass, and fabrics of western Europe for the native furs; yet it is likely that they were built by the viking folk and that from the beginning they were peopled largely by them, for the fortunes of Frisia declined rapidly soon after their establish-

97

ment and the northern people were left to dispute among themselves for the control of the profitable trade-route leading across Sleswig to the Baltic and to the Vik. (1) The supreme economic importance of this route was demonstrated more than once in northern history, as when a later king of Denmark, Harald Gormsson, and the then ruler of Norway, Jarl Haakon, united in 974 to defend this Danevirke district against the attacks of the German emperor, Otto II, but its immediate interest is that even in this early period at the beginning of the tenth century there was a struggle between the Swedes and the Danes for the

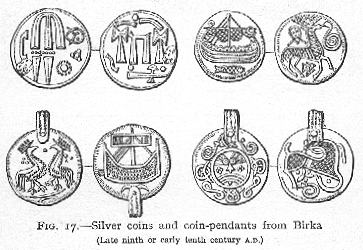

1. It was Knut Stjerna, Hist. Tidskrift f. Skåneland, III (1909), p. 176 ff., who first suggested the Frisian origin of Birka, and there is something to be said in favour of his view; thus there were some distinctive pottery jugs found there that have exact parallels in Frisia, and the resemblance of the well-known Birka coins (Fig. 17) to Frisian prototypes has been demonstrated by P. Hauberg. It is not, however, by any means certain that the relatively common place-name Björkö, which occurs not only in Sweden but in Norway, is of Frisian origin and betrays, as is sometimes said, the northern marts of this merchant-folk, for only at the Mälar Björkö is there any sign of an important settlement in the ninth and tenth centuries, and it is possible, as E. Wessén has suggested, that the word is simply an Old Swedish form for Birch Island. Note that H. Schück, Birka, 1910, and, more recently, S. Lindqvist, Fornvännen, 1926, p. 4 ff., have denied the Frisian origin of Birka. For this town, see Lindqvist excellent little guide, Björkö, Svenska fornminnesplatser 2, Stockholm, 1930, and A. Schück, Det svenska stadväsendets uppkomst, Stockholm, 1926, p. 51 ff. and p. 348 ff., a most important book. Hedeby also can show pottery that has Frisian analogies (I refer to the curious 'bar-lip' fragments); for this town, see O. Scheel and P. Paulsen, Schleswig-Haithabu, Kiel, 1930 (containing all the historical references to Hedeby and a full bibliography of recent literature). Here the problem of its age and origin is made all the more difficult in that it is bound up with the theories concerning the archaeology and history of the Danevirke. The argument that because the site lies south of Godfred's dyke Hedeby must be a non-Danish foundation is of no importance, as the existence of a frontier does not preclude further territorial expansion; moreover, E. Wadstein, Fornvännen, 1927, p. 253 , has tried (I do not think successfully) to prove that it is the Kurvirke, lying south of Hedeby, and not the Vestervold to the north, that was Godfred's original fortification. Professor Lindqvist will have it, Fornvännen, 1926, p. 1, that Hedeby is not older than about A.D. 900 and that it was founded by invading Swedes, being planned on the model of Birka; but I have seen an oval brooch among the Hedeby finds that ought to be older than 900, and I should like to stress the very important evidence of the Norwegian Ottar (see above) who knew Haethan, which must surely be Hedeby, as a Danish town before the end of the ninth century. Lindqvist would no doubt retort that this Danish town was on the north of the Slien, probably on the site of the modern Sleswig, and not the Hedeby in the 'semicircle'; Wadstein, however, opposes this and declares that Hedeby in the semicircle was the early Sleswig (Sliesthorp or Sliaswich), Fornvännen, 1927, p. 255.

98

possession of Hedeby. The first hint of this rivalry is to be discovered in an account of certain Danish kings given in an historical treatise that it is now proper to cite.

The Frankish chronicles have nothing to say of the kings of Denmark in the period immediately after 873, and it is not until the beginning of the tenth century that Danish royalties are mentioned again. The new source is the Hamburg Church History of Adam of Bremen, and his testimony, although brief, is of more than ordinary interest in that he derived his facts, as he himself remarks, from the mouth of Svein II Estridsen, king of Denmark, about the year 1075. According to this authority a king named Helgi ruled in Denmark about A.D. 900, and this Helgi was succeeded by an Olof who came from Sweden and seized the kingdom by force. Olof's sons, Knubbe and Gurd, reigned after him, and in due course the throne passed into the possession of Knubbe's son who was called Sigtryg; but when he had reigned a short time Hardegon Svennson, coming from 'Nordmannia', wrested the kingdom from him. But, adds Adam, it is uncertain whether all these kings reigned in succession one after the other or whether some of them ruled at the same time.

The significance of the statement that Olof came from Sweden is not immediately obvious, but the fact that there is such a large number of objects of patently Scandinavian origin and of about his date among the Hedeby finds suggests at once that it was in fact at Hedeby that he established his Swedish invaders, having possessed himself of this district, and the town dominating the old Frisian trade-route, by right of conquest. On this point there is something more than the witness of Adam of Bremen. For Widukind's chronicle relates how the Emperor Henry I fought against Knubbe (here called Chuba), Olof's son, to punish him for piratical raids on the Frisian coast, (1) and this Knubbe's name, together with that of his son, Sigtryg, is inscribed on two memorial stones near Hedeby, one of which was set up on the coast of Haddeby Nor and betrays Swedish dialectical peculiarities. (2)

The fate of the Swedish colony at Hedeby when Sigtryg was defeated and slain by the invading Hardegon in the early

1. M.G.H. ( Pertz), SS. III, p. 435.

2. L. Wimmer, Danske Runemindesmaerker, 70. It is also related in the greater Olaf Tryggvason saga that Knubbe was slain by the Danish king Gorm ( Fornmannasögur, I, 115); this is a late and dubious tradition, though it is likely enough that Gorm did war against the Hedeby Swedes.

<< Previous Page Next Page >>

© 2004-2007 Northvegr.

Most of the material on this site is in the public domain. However, many people have worked very hard to bring these texts to you so if you do use the work, we would appreciate it if you could give credit to both the Northvegr site and to the individuals who worked to bring you these texts. A small number of texts are copyrighted and cannot be used without the author's permission. Any text that is copyrighted will have a clear notation of such on the main index page for that text. Inquiries can be sent to info@northvegr.org. Northvegr™ and the Northvegr symbol are trademarks and service marks of the Northvegr Foundation.

|