[52] while elsewhere they were naked. Karlsefni and his companions cast anchor, and lay there during their absence; and when they came again, one of them carried a bunch of grapes and the other an ear of new-sown wheat. They went on board the ship, whereupon Karlsefni and his followers held on their way, until they came to where the coast was indented with bays. They stood into a bay with their ships. There was an island out at the mouth of the bay, about which there were strong currents, wherefore they called it Straumey [Stream Isle]. There were so many birds there that it was scarcely possible to step between the eggs. They sailed through the firth, and called it Straumfiord [Streamfirth], and carried their cargoes ashore from the ships, and established themselves there. They had brought with them all kinds of live-stock. It was a fine country there. There were mountains thereabouts. They occupied themselves exclusively with the exploration of the country. They remained there during the winter, and they had taken no thought for this during the summer. The fishing began to fail, and they began to fall short of food. Then Thorhall the Huntsman disappeared. They had already prayed to God for food, but it did not come as promptly as their necessities seemed to demand. They searched for Thorhall for three half-days, and found him on a projecting crag. He was lying there and looking up at the sky, with mouth and nostrils agape, and mumbling something. They asked him why he had gone thither; he replied that this did not concern anyone. They asked him then to go home with [53] them, and he did so. Soon after this a whale appeared there, and they captured it, and flensed it, and no one could tell what manner of whale it was; and when the cooks had prepared it they ate of it, and were all made ill by it. Then Thorhall, approaching them, said: "Did not the Red-beard (49) prove more helpful than your Christ? This is my reward for the verses which I composed to Thor, the Trustworthy; seldom has he failed me." When the people heard this they cast the whale down into the sea, and made their appeals to God. The weather then improved, and they could now row out to fish, and thenceforward they had no lack of provisions, for they could hunt game on the land, gather eggs on the island, and catch fish from the sea.

CONCERNING KARLSEFNI AND THORHALL

It is said that Thorhall wished to sail to the northward beyond Wonder-strands, in search of Wineland, while Karlsefni desired to proceed to the southward, off the coast. Thorhall prepared for his voyage out below the island, having only nine men in his party, for all the remainder of the company went with Karlsefni. And one day when Thorhall was carrying water aboard his ship, and was drinking, he recited this ditty:

When I came, these brave men told me,

Here the best of drink I'd get,

Now with water-pail behold me,--

Wine and I are strangers yet.

Stooping at the spring, I've tested

All the wine this land affords;

Of its vaunted charms divested,

Poor indeed are its rewards.

[54] And when they were ready, they hoisted sail; whereupon Thorhall recited this ditty:

Comrades, let us now be faring

Homeward to our own again!

Let us try the sea-steed's daring,

Give the chafing courser rein.

Those who will may bide in quiet,

Let them praise their chosen land,

Feasting on a whale-steak diet,

In their home by Wonder-strand. (49a)

Then they sailed away to the northward past Wonder-strands and Keelness, intending to cruise to the westward around the cape. They encountered westerly gales, were driven ashore in Ireland, where they were grievously maltreated and thrown into slavery. There Thorhall lost his life, according to that which traders have related.

It is now to be told of Karlsefni, that he cruised southward off the coast, with Snorri and Biarni, and their people. They sailed for a long time, and until they came at last to a river which flowed down from the land into a lake, and so into the sea. There were great bars at the mouth of the river, so that it could only be entered at the height of the flood-tide. Karlsefni and his men sailed into the mouth of the river, and called it there Hop [a small land-locked bay]. They found self-sown wheat-fields on the land there; wherever there were hollows, and wherever there was hilly ground, there were vines (50). Every brook there was full of fish. They dug [55] pits on the shore where the tide rose highest, and when the tide fell there were halibut (51) in the pits. There were great numbers of wild animals of all kinds in the woods. They remained there half a month, and enjoyed themselves, and kept no watch. They had their livestock with them. Now one morning early when they looked about them they saw a great number of skin-canoes, and staves (52) were brandished from the boats, with a noise like flails, and they were revolved in the same direction in which the sun moves. Then said Karlsefni: "What may this betoken?" Snorri, Thorbrand's son, answered him: "It may be that this is a signal of peace, wherefore let us take a white shield (53) and display it." And thus they did. Thereupon the strangers rowed toward them, and went upon the land, marvelling at those whom they saw before them. They were swarthy men and ill-looking, and the hair of their heads was ugly. They had great eyes, and were broad of cheek (54). They tarried there for a time looking curiously at the people they saw before them, and then rowed away, and to the southward around the point.

Karlsefni and his followers had built their huts above the lake, some of their dwellings being near the lake, and others farther away. Now they remained there that winter. No snow came there, and all of their live-stock lived by grazing (55). And when spring opened they discovered, early one morning, a great number of skin-canoes rowing from the south past the cape, so numerous that it looked as if coals had been scattered broadcast out before the bay; and on every boat staves were waved. [56]

Thereupon Karlsefni and his people displayed their shields and when they came together they began to barter with each other. Especially did the strangers wish to buy red cloth, for which they offered in exchange peltries and quite grey skins. They also desired to buy swords and spears, but Karlsefni and Snorri forbade this. In exchange for perfect unsullied skins, the Skrellings would take red stuff a span in length, which they would bind around their heads. So their trade went on for a time, until Karlsefni and his people began to grow short of cloth, when they divided it into such narrow pieces that it was not more than a finger's breadth wide, but the Skrellings still continued to give just as much for this as before, or more.

It so happened that a bull, belonging to Karlsefni and his people, ran out from the woods, bellowing loudly. This so terrified the Skrellings, that they sped out to their canoes, and then rowed away to the southward along the coast. For three entire weeks nothing more was seen of them. At the end of this time, however, a great multitude of Skrelling boats was discovered approaching from the south, as if a stream were pouring down, and all of their staves were waved in a direction contrary to the course of the sun, and the Skrellings were all tittering loud cries. Thereupon Karlsefni and his men took red shields (52) and displayed them. The Skrellings sprang from their boats, and they met then, and fought together. There was a fierce shower of missiles, for the Skrellings had war-slings. Karlsefni and Snorri observed that the Skrellings raised up on a pole a great [57] ball-shaped body, almost the size of a sheep's belly, and nearly black in colour, and this they hurled from the pole upon the land above Karlsefni's followers, and it made a frightful noise where it fell. Whereat a great fear seized upon Karlsefni and all his men, so that they could think of nought but flight, and of making their escape up along the river bank, for it seemed to them that the troop of the Skrellings was rushing towards them from every side, and they did not pause until they came to certain jutting crags, where they offered a stout resistance. Freydis came out, and seeing that Karlsefni and his men were fleeing, she cried: "Why do ye flee from these wretches, such worthy men as ye, when, meseems, ye might slaughter them like cattle. Had I but a weapon, methinks, I would fight better than any one of you!" They gave no heed to her words. Freydis sought to join them, but lagged behind, for she was not hale; she followed them, however, into the forest, while the Skrellings pursued her; she found a dead man in front of her; this was Thorbrand, Snorri's son, his skull cleft by a flat stone; his naked sword lay beside him; she took it up, and prepared to defend herself with it. The Skrellings then approached her, whereupon she stripped down her shift, and slapped her breast with the naked sword. At this the Skrellings were terrified and ran down to their boats, and rowed away. Karlsefni and his companions, however, joined her and praised her valour. Two of Karlsefni's men had fallen and a great number of the Skrellings. Karlsefni's party had been overpowered by dint of superior numbers. They now returned to. their [58] dwellings, and bound up their wounds, and weighed carefully what throng of men that could have been, which had seemed to descend upon them from the land; it now seemed to them that there could have been but the one party, that which came from the boats, and that the other troop must have been an ocular delusion. The Skrellings, however, found a dead man, and an axe lay beside him. One of their number picked up the axe, and struck at a tree with it, and one after another [they tested it], and it seemed to them to be a treasure, and to cut well; then one of their number seized it, and hewed at a stone with it, so that the axe broke, whereat they concluded that it could be of no use, since it would not withstand stone, and they cast it away.

It now seemed clear to Karlsefni and his people that although the country thereabouts was attractive, their life would be one of constant dread and turmoil by reason of the [hostility of the] inhabitants of the country, so they forthwith prepared to leave, and determined to return to their own country. They sailed to the northward off the coast, and found five Skrellings, clad in skin-doublets, lying asleep near the sea. There were vessels beside them containing animal marrow, mixed with blood. Karlsefni and his company concluded that they must have been banished from their own land. They put them to death. They afterwards found a cape, upon which there was a great number of animals, and this cape looked as if it were one cake of dung, by reason of the animals which lay there at night. They now arrived again at Streamfirth, where they found great abundance of all those things

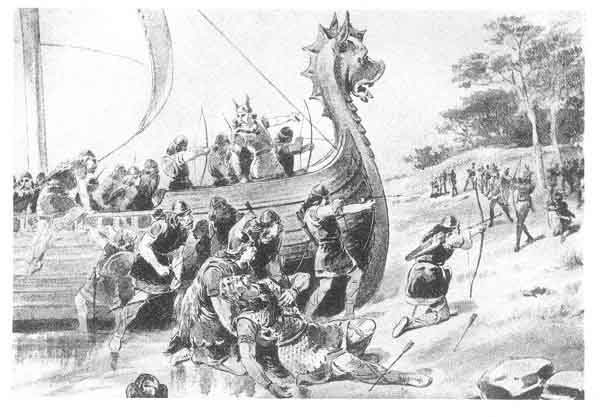

DEATH OF THORVALD ERIKSON. (From a drawing by Kendrick.) THORVALD, a son of Eric the Red, was a man cast in a mould as heroic as that from which issued his historically better known brother, Leif Erikson. To him the credit is due of having been with Karlsefni, the first white man to explore the American coast south of what is now Massachusetts. His death from an arrow wound, received at the hand,, of the Skrellings (Indians), was the first tragedy enacted in the settlement of the New World, and his dying words were prophetic of the greatness which the country would some day attain because of its fruitfulness. |

[59] of which they stood in need. Some men say that Biarni and Freydis remained behind here with a hundred men, and went no further; while Karlsefni and Snorri proceeded to the southward with forty men, tarrying at Hop barely two months, and returning again the same summer. Karlsefni then set out with one ship in search of Thorhall the Huntsman, but the greater part of the company remained behind. They sailed to the northward around Keelness, and then bore to the westward, having land to the larboard. The country there was a wooded wilderness, as far as they could see, with scarcely an open space; and when they had journeyed a considerable distance, a river flowed down from the east toward the west. They sailed into the mouth of the river, and lay to by the southern bank.

THE SLAYING OF THORVALD, ERIC'S SON

It happened one morning that Karlsefni and his companions discovered in an open space in the woods above them, a speck, which seemed to shine toward them, and they shouted at it; it stirred and it was a Uniped (56), who skipped down to the bank of the river by which they were lying. Thorvald, a son of Eric the Red, was sitting at the helm, and the Uniped shot an arrow into his inwards. Thorvald drew out the arrow, and exclaimed: "There is fat around my paunch; we have hit upon a fruitful country, and yet we are not like to get much profit of it." Thorvald died soon after from this wound. Then the Uniped ran away back toward the north. Karlsefni and his men pursued him, and saw him from time [60] to time. The last they saw of him, he ran down into a creek. Then they turned back; whereupon one of the men recited this ditty:

Eager, our men, up hill, down dell,

Hunted a Uniped;

Hearken, Karlsefni, while they tell

How swift the quarry fled!

Then they sailed away back toward the north, and believed they had got sight of the land of the Unipeds; nor were they disposed to risk the lives of their men any longer. They concluded that the mountains of Hop, and those which they had now found, formed one chain, and this appeared to be so because they were about an equal distance removed from Streamfirth, in either direction. They sailed back, and passed the third winter at Streamfirth. Then the men began to divide into factions, of which the women were the cause; and those who were without wives endeavoured to seize upon the wives of those who were married, whence the greatest trouble arose. Snorri, Karlsefni's son, was born the first autumn, and he was three winters' old when they took their departure. When they sailed away from Wineland, they had a southerly wind, and so came upon Markland, where they found five Skrellings, of whom one was bearded, two were women, and two were children. Karlsefni and his people took the boys, but the others escaped, and these Skrellings sank down into the earth. They bore the lads away with them, and taught them to speak, and they were baptized. They said that their mother's name was Vætilldi, and their [61] father's Uvægi. They said that kings governed the Skrellings, one of whom was called Avalldamon, and the other Valldidida (57). They stated, that there were no houses there, and that the people lived in caves or holes. They said that there was a land on the other side over against their country, which was inhabited by people who wore white garments, and yelled loudly, and carried poles before them, to which rags were attached; and people believe that this must have been Hvitramannaland [White-men's-land], or Ireland the Great (58). Now they arrived in Greenland, and remained during the winter with Eric the Red.

Biarni, Grimolf's son, and his companions were driven out into the Atlantic, and came into a sea, which was filled with worms, (58a) and their ship began to sink beneath them. They had a boat which had been coated with seal-tar; this the sea-worm does not penetrate. They took their places in this boat, and then discovered that it would not hold them all. Then said Biarni: "Since the boat will not hold more than half of our men, it is my advice, that the men who are to go in the boat be chosen by lot, for this selection must not he made according to rank." This seemed to them all such a manly offer that no one opposed it. So they adopted this plan, the men casting lots; and it fell to Biarni to go in the boat, and half of the men with him, for it would not hold more. But when the men were come into the boat an Icelander, who was in the ship, and who had accompanied Biarni [62] from Iceland, said: "Dost thou intend, Biarni, to forsake me here?" "It must be even so," answers Biarni. "Not such was the promise thou gavest my father," he answers, "when I left Iceland with thee, that thou wouldst thus part with me, when thou saidst that we should both share the same fate." "So be it, it shall not rest thus," answered Biarni; "do thou come hither, and I will go to the ship, for I see that thou art eager for life." Biarni thereupon boarded the ship, and this man entered the boat, and they went their way, until they came to Dublin in Ireland, and there they told this tale; now it is the belief of most people that Biarni and his companions perished in the maggot-sea, for they were never heard of afterward.

KARLSEFNI AND HIS WIFE THURID'S ISSUE.

The following summer Karlsefni sailed to Iceland and Gudrid with him, and he went home to Reyniness (59). His mother believed that he had made a poor match, and she was not at home the first winter. However, when she became convinced that Gudrid was a very superior woman, she returned to her home, and they lived happily together. Hallfrid was a daughter of Snorri, Karlsefni's son, she was the mother of Bishop Thorlak, Runolf's son (60). They had a son named Thorbiorn, whose daughter's name was Thorunn [she was] Bishop Biorn's mother. Thorgeir was the name of a son of Snorri, Karlsefni's son, [he was] the father of Ingveld, mother of Bishop Brand the Elder. Steinunn was a daughter of Snorri, Karlsefni's son, who married Einar, a son of [63] Grundar-Ketil, a son of Thorvald Crook, a son of Thori of Espihol. Their son was Thorstein the Unjust, he was the father of Gudrun, who married Jorund of Keldur. Their daughter was Halla, the mother of Flosi, the father of Valgerd, the mother of Herra Erlend, the Stout, the father of Herra Hauk the Lawman. Another daughter of Flosi was Thordis, the mother of Fru Ingigerd the Mighty. Her daughter was Fru Hallbera, Abbess of Reyniness at Stad. Many other great people in Iceland are descended from Karlsefni and Thurid, who are not mentioned here. God be with us, Amen!

Notes:

(49) i. e. Thor. It has been suggested, that Thorhall's persistent adherence to the heathen faith may have led to his being regarded with ill-concealed disfavor. [Back]

(49a) The prose sense of the verse is: Let us return to our countrymen, leaving those, who like the country here, to cook their whale on Wonder-strands. [Back]

(50) There can be little doubt that this "self-sown wheat" was wild rice. The habit of this plant, its growth in low ground as here described, and the head, which has a certain resemblance to that of cultivated small grain, especially oats, seem clearly to confirm this view. The explorers probably had very slight acquaintance with cultivated grain, and might on this account more readily confuse this wild rice with wheat. [140] There is not, however, the slightest foundation for the theory that this "wild wheat" was Indian corn, a view which has been advanced by certain writers. Indian corn was a grain entirely unknown to the explorers, and they could not by any possibility have confused it with wheat, even if they had found this corn growing wild, a conjecture for which there is absolutely no support whatever. The same observation as that made by the Wineland discoverers was recorded by Jacques Cartier five hundred years later, concerning parts of the Canadian territory which he explored. It is no less true that this same explorer found grapes growing wild, in a latitude as far north as that of Nova Scotia, and, as would appear from the record, in considerable abundance. Again, in the following century, we have an account of an exploration of the coast of Nova Scotia, in which the following passage occurs: "All the ground between the two Riuers was without Wood, and was good fat earth hauing seueral sorts of Berries growing thereon, as Gooseberry, Straw-berry, Hyndberry, Rasberry, and a kinde of Red-wine-berry: As also some sorts of Graine, as Pease, some eares of Wheat, Barley, and Rye, growing there wild," etc. [Purchas his Pilgrimes, London, 1625.] [Back]

(51) Lit. "holy fish." The origin of the name is not known. Prof. Maurer suggests that it may have been derived from some folk-tale concerning St, Peter, but adds that such a story, if it ever existed, has not been preserved. [Back]

(52) It is not clear what the exact nature of these staves may have been. These "staves" may have had a certain likeness to the long oars of the inhabitants of Newfoundland, described in a notice of date July 29th, 1612: "They haue two kinde of Oares, one is about foure foot long of one peece of Firre; the other is about ten foot long made of two peeces, one being as long, big and round as a halfe Pike made of Beech wood, which by likelihood they made of a Biskin Oare, the other is the blade of the Oare, which is let into the end of the long one slit, and whipped very strongly. The short one they use as a Paddle, and the other as in Oare." [Purchas his Pilgrimes, London, 1625.] [Back]

(53) The white shield, called the "peace-shield," was displayed by those who wished to indicate to others with whom [141] they desired to meet that their intentions were not hostile, as in Magnus Barefoot's Saga, "the barons raised aloft a white peace-shield." The red shield, on the other hand, was the war-shield, a signal of enmity, as Sinfiotli declares in the Helgi song, "Quoth Sinfiotli, hoisting a red shield to the yard, . . . 'tell it this evening. . . . that the Wolfings are coming from the East, lusting for war.'" The use of a white flag-of-truce for a purpose similar to that for which Snorri recommended the white shield, is described in the passage quoted in note 52, "Nouember the sixt two Canoas appeared, and one man alone coming towards vs with a Flag in his hand of a Wolfes skin, shaking it and making a loud noise, which we took to be for a parley, whereupon a white Flag was put out, and the Barke and Shallop rowed towards them." [Purchas his Pilgrimes.] [Back]

(54) The natives of the country here described were called by the discoverers, as we read, Skrælingjar; since this was the name applied by the Greenland colonists to the Eskimo, it has generally been concluded that the Skrælingjar of Wineland were Eskimo. Prof. Storm has recently pointed out that there may be sufficient reason for caution in hastily accepting this conclusion, and he would identify the inhabitants of Wineland with the Indians, adducing arguments philological and ethnographical to support his theory. The description of the savages of Newfoundland, given in the passage in Purchas' "Pilgrims," already cited, offers certain details which coincide with the description of the Skrellings, contained in the saga. These savages are said by the English explorers to be "full-eyed, of black colour; the colour of their hair was diners, some blacke, some browne, and some yellow, and their faces something flat and broad." Other details, which are given on the same authority, have not been noted by the Icelandic explorers, and one statement, at least, "they haue no beards," is directly at variance with the saga statement concerning the Skrellings seen by the Icelanders on their homeward journey. The similarity of description may be a mere accidental coincidence, and it by no means follows that the English writer and Karlsefni's people saw the same people, or even a kindred tribe. [Back]

(55) John Guy, in a letter to Master Slany, the Treasurer and [142] "Counsell" of the New-found-land Plantation writes: "The doubt that haue bin made of the extremity of the winter season in these parts of New-found-land are found by our experience causelesse; and that not onely men may safely inhabit here without any neede of stoue, but Nauigation may be made to and fro from England to these parts at any time of the yeare. . . . Our Goates haue liued here all this winter; and there is one lustie kidde, which was yeaned in the dead of winter." [Purchas his Pilgrimes, vol. iv, p. 1878.] [Back]

(56) i. e., a One-footer, a man with one leg or foot. In the Flatey Book Thorvald's death is less romantically described. The mediæval belief in a country in which there lived a race of one-legged men, was not unknown in Iceland, for mention is made in Rimbegla, of "a people of Africa called One-footers, the soles of whose feet are so large that they shade themselves with these against the heat of the sun when they sleep." It is apparent from the passages from certain Icelandic works already cited, that, at the time these works were written, Wineland was supposed to be in some way connected with Africa. Whether this notice of the finding of a Uniped in the Wineland region may have contributed to the adoption of such a theory, it is, of course, impossible to determine. The reports which the explorers brought back of their having seen a strange man, who, for some reason not now apparent, they believed to have but one leg, may, because Wineland was held to be contiguous to Africa, have given rise to the conclusion that this strange man was indeed a Uniped, and that the explorers had hit upon the African "land of the Unipeds." It has also been suggested that the incident of the appearance of the "One-footer" may have found its way into the saga to lend an additional adornment to the manner of Thorvald's taking-off. It is a singular fact that Jacques Cartier brought back from his Canadian explorations reports not only of a land peopled by a race of one-legged folk, but also of a region in those parts where the people were "as white as those of France." [Back]

(57) These words, it has been supposed, might afford a clue to the language of the Skrellings, which would aid in determining their race. In view not only of the fact, that they probably [143] passed through many strange mouths before they were committed to writing, but also that the names are not the same in the different manuscripts, they appear to afford very equivocal testimony. Especially is the soft melody of these Skrelling-words altogether different from the harsh gutteral sounds of the Eskimo language. We must therefore refer for the derivation of these words to the Indians, whom we know in this region in later times. The inhabitants, whom the discoverers of the sixteenth century found in Newfoundland, and who called themselves "Beothuk" [i. e., men], received from the Europeans the name of Red Indians, because they smeared themselves with ochre; they have now been exterminated, partly by the Europeans, partly by the Micmac Indians, who in the last century wandered into Newfoundland from New Brunswick. Of their language only a few remnants have been preserved, but still enough to enable us to form a tolerably good idea of it.

"Even as there are on the north-western coast of North America races which seem to me to occupy a place between the Indian and Eskimo, so it appears to me not sufficiently proven, that the now extinct race on America's east coast, the Beothuk, were Indians. Their mode of life and belief have many points of resemblance, by no means unimportant, with the Eskimo and especially with the Angmagsalik. It is not necessary to particularize these here, but I wish to direct attention to the possibility, that in the Beothuk we may perhaps have one of the transition links between the Indian and the Eskimo." [Back]

(58) The sum of information which we possess concerning

White-men's-land or Ireland the Great, is comprised in this passage and in the

quotation from Landnáma. It does not seem possible from these very vague

notices to arrive at any sound conclusion concerning the location of this country.

Rafn concludes that it must have been the southern portion of the eastern coast

of North America. Vigfusson and Powell suggest that the inhabitants of this

White-men's-land were "Red Indians;" with these, they say, "the

Norsemen never came into actual contact, or we should have a far more vivid

description than this, and their land would bear a more appropriate title."

Storm, in his "Studier over Vinlandsreiserne," would regard [144]

"Greater Ireland" as a semi-fabulous land, tracing its quasi-historical

origin to the Irish visitation of Iceland prior to the Norse settlement. No

one of these theories is entirely satisfactory, and the single fact which seems

to be reasonably well established is that "Greater Ireland" was to

the Icelandic scribes terra incognita. [Back]

(58a) This reference is to the toredo, or ship worm, that

bores into wood and is often a source of danger to unsheathed vessels. [Back]

(59) The modern Reynistadr is situated in Northern Iceland, a short distance to the southward of Skaga-firth. Glaumbœr, as it is still called, is somewhat farther south, but hard by. [Back]

(60) Thorlak Runolfsson was the third bishop of Skálholt. He was consecrated bishop in the year 1118, and died 1133. Biorn Gilsson was the third bishop of Hólar, the episcopal seat of northern Iceland; he became bishop in 1147, and died in the year 1162. Bishop Biorn's successor was Brand Sæmundsson, "Bishop Brand the Elder," who died in the year 1201. [Back]

© 2004-2007 Northvegr.

Most of the material on this site is in the public domain. However, many people have worked very hard to bring these texts to you so if you do use the work, we would appreciate it if you could give credit to both the Northvegr site and to the individuals who worked to bring you these texts. A small number of texts are copyrighted and cannot be used without the author's permission. Any text that is copyrighted will have a clear notation of such on the main index page for that text. Inquiries can be sent to info@northvegr.org. Northvegr™ and the Northvegr symbol are trademarks and service marks of the Northvegr Foundation.

|