|

|

| Thumbling.

There was once a poor peasant who sat in the evening by the hearth and poked the fire, and his wife sat and spun. Then said he, how sad it is that we have no children. With us all is so quiet, and in other houses it is noisy and lively. Yes, replied the wife, and sighed, even if we had only one, and it were quite small, and only as big as a thumb, I should be quite satisfied, and we would still love it with all our hearts. Now it so happened that the woman fell ill, and after seven months gave birth to a child, that was perfect in all its limbs, but no longer than a thumb. Then said they, it is as we wished it to be, and it shall be our dear child. And because of its size, they called it thumbling. Though they did not let it want for food, the child did not grow taller, but remained as it had been at the first. Nevertheless it looked sensibly out of its eyes, and soon showed itself to be a wise and nimble creature, for everything it did turned out well.

|

Daumesdick

Es war ein armer Bauersmann, der saß abends beim Herd und schürte das Feuer, und die Frau saß und spann. Da sprach er "wie ists so traurig, daß wir keine Kinder haben! es ist so still bei uns, und in den andern Häusern ists so laut und lustig." "Ja," antwortete die Frau und seufzte, "wenns nur ein einziges wäre, und wenns auch ganz klein wäre, nur Daumens groß, so wollte ich schon zufrieden sein; wir hättens doch von Herzen lieb." Nun geschah es, daß die Frau kränklich ward und nach sieben Monaten ein Kind gebar, das zwar an allen Gliedern vollkommen, aber nicht länger als ein Daumen war. Da sprachen sie "es ist, wie wir es gewünscht haben, und es soll unser liebes Kind sein," und nannten es nach seiner Gestalt Daumesdick. Sie ließens nicht an Nahrung fehlen, aber das Kind ward nicht größer, sondern blieb, wie es in der ersten Stunde gewesen war; doch schaute es verständig aus den Augen und zeigte sich bald als ein kluges und behendes Ding, dem alles glückte, was es anfing. |

|

One day the peasant was getting ready to go into the forest to cut wood, when he said as if to himself, how I wish that there was someone who would bring the cart to me. Oh father, cried thumbling, I will soon bring the cart, rely on that. It shall be in the forest at the appointed time. The man smiled and said, how can that be done, you are far too small to lead the horse by the reins. That's of no consequence, father, if my mother will only harness it, I shall sit in the horse's ear and call out to him how he is to go. Well, answered the man, for once we will try it.

|

Der Bauer machte sich eines Tages fertig, in den Wald zu gehen und Holz zu fällen, da sprach er so vor sich hin "nun wollt ich, daß einer da wäre, der mir den Wagen nachbrächte." "O Vater," rief Daumesdick, "den Wagen will ich schon bringen, verlaßt Euch drauf, er soll zur bestimmten Zeit im Walde sein." Da lachte der Mann und sprach "wie sollte das zugehen, du bist viel zu klein, um das Pferd mit dem Zügel zu leiten." "Das tut nichts, Vater, wenn nur die Mutter anspannen will, ich setze mich dem Pferd ins Ohr und rufe ihm zu, wie es gehen soll." "Nun," antwortete der Vater, "einmal wollen wirs versuchen." |

|

When the time came, the mother harnessed the horse, and placed thumbling in its ear, and then the little creature cried, gee up, gee up. Then it went quite properly as if with its master, and the cart went the right way into the forest. It so happened that just as he was turning a corner, and the little one was crying, gee up, two strange men came towards him. My word, said one of them, what is this. There is a cart coming, and a driver is calling to the horse and still he is not to be seen. That can't be right, said the other, we will follow the cart and see where it stops. The cart, however, drove right into the forest, and exactly to the place where the wood had been cut. When thumbling saw his father, he cried to him, do you see, father, here I am with the cart, now take me down. The father got hold of the horse with his left hand and with the right took his little son out of the ear. Thumbling sat down quite merrily on a straw, but when the two strange men saw him, they did not know what to say for astonishment. Then one of them took the other aside and said, listen, the little fellow would make our fortune if we exhibited him in a large town, for money. We will buy him. They went to the peasant and said, sell us the little man. He shall be well treated with us. No, replied the father, he is the apple of my eye, and all the money in the world cannot buy him from me. Thumbling, however, when he heard of the bargain, had crept up the folds of his father's coat, placed himself on his shoulder, and whispered in his ear, father do give me away, I will soon come back again. Then the father parted with him to the two men for a handsome sum of money. Where will you sit, they said to him. Oh just set me on the rim of your hat, and then I can walk backwards and forwards and look at the country, and still not fall down. They did as he wished, and when thumbling had taken leave of his father, they went away with him. They walked until it was dusk, and then the little fellow said, do take me down, it is necessary. Just stay up there, said the man on whose hat he sat, it makes no difference to me. The birds sometimes let things fall on me. No, said thumbling, I know what's manners, take me quickly down. The man took his hat off, and put the little fellow on the ground by the wayside, and he leapt and crept about a little between the sods, and then he suddenly slipped into a mousehole which he had sought out. Good evening, gentlemen, just go home without me, he cried to them, and mocked them. They ran thither and stuck their sticks into the mousehole, but it was all in vain. Thumbling crept still farther in, and as it soon became quite dark, they were forced to go home with their vexation and their empty purses.

|

Als die Stunde kam, spannte die Mutter an und setzte Daumesdick ins Ohr des Pferdes, und dann rief der Kleine, wie das Pferd gehen sollte, "jüh und joh! hott und har!, Da ging es ganz ordentlich als wie bei einem Meister, und der Wagen fuhr den rechten Weg nach dem Walde. Es trug sich zu, als er eben um eine Ecke bog und der Kleine "har, har!" rief, daß zwei fremde Männer daherkamen. "Mein," sprach der eine, "was ist das? da fährt ein Wagen, und ein Fuhrmann ruft dem Pferde zu, und ist doch nicht zu sehen." "Das geht nicht mit rechten Dingen zu," sagte der andere, "wir wollen dem Karren folgen und sehen, wo er anhält." Der Wagen aber fuhr vollends in den Wald hinein und richtig zu dem Platze, wo das Holz gehauen ward. Als Daumesdick seinen Vater erblickte, rief er ihm zu "siehst du, Vater, da bin ich mit dem Wagen, nun hol mich runter." Der Vater faßte das Pferd mit der Linken und holte mit der Rechten sein Söhnlein aus dem Ohr, das sich ganz lustig auf einen Strohhalm niedersetzte. Als die beiden fremden Männer den Daumesdick erblickten, wußten sie nicht, was sie vor Verwunderung sagen sollten. Da nahm der eine den andern beiseit und sprach "hör, der kleine Kerl könnte unser Glück machen, wenn wir ihn in einer großen Stadt für Geld sehen ließen, wir wollen ihn kaufen." Sie gingen zu dein Bauer und sprachen "verkauft uns den kleinen Mann" er solls gut bei uns haben." "Nein," antwortete der Vater, "es ist mein Herzblatt, und ist mir für alles Gold in der Welt nicht feil!" Daumesdick aber, als er von dem Handel gehört, war an den Rockfalten seines Vaters hinaufgekrochen, stellte sich ihm auf die Schulter und wisperte ihm ins Ohr "Vater, gib mich nur hin, ich will schon wieder zurückkommen." Da gab ihn der Vater für ein schönes Stück Geld den beiden Männern hin. "Wo willst du sitzen?, sprachen sie zu ihm. "Ach, setzt mich nur auf den Rand von eurem Hut, da kann ich auf und ab spazieren und die Gegend b etrachten, und falle doch nicht herunter." Sie taten ihm den Willen, und als Daumesdick Abschied von seinem Vater genommen hatte, machten sie sich mit ihm fort. So gingen sie, bis es dämmrig ward, da sprach der Kleine "hebt mich einmal herunter, es ist nötig." "Bleib nur droben" sprach der Mann, auf dessen Kopf er saß, "ich will mir nichts draus machen, die Vögel lassen mir auch manchmal was drauf fallen." "Nein," sprach Daumesdick, "ich weiß auch, was sich schickt, hebt mich nur geschwind herab." Der Mann nahm den Hut ab und setzte den Kleinen auf einen Acker am Weg, da sprang und kroch er ein wenig zwischen den Schollen hin und her, dann schlüpfte er pIötzlich in ein Mausloch, das er sich ausgesucht hatte. "Guten Abend, ihr Herren, geht nur ohne mich heim," rief er ihnen zu, und lachte sie aus. Sie liefen herbei und stachen mit Stöcken in das Mausloch, aber das war vergebliche Mühe, Daumesdick kroch immer weiter zurück, und da es bald ganz dunkel ward, so mußten sie mit Ärger und mit leerem Beutel wieder heim wandern. |

| When thumbling saw that they were gone, he crept back out of the subterranean passage. It is so dangerous to walk on the ground in the dark, said he, how easily a neck or a leg is broken. Fortunately he stumbled against an empty snail-shell. Thank God, said he, in that I can pass the night in safety. And got into it. Not long afterwards, when he was just going to sleep, he heard two men go by, and one of them was saying, how shall we set about getting hold of the rich pastor's silver and gold. I could tell you that, cried thumbling, interrupting them. What was that, said one of the thieves in fright, I heard someone speaking. They stood still listening, and thumbling spoke again, and said, take me with you, and I'll help you. But where are you. Just look on the ground, and observe from whence my voice comes, he replied. There the thieves at length found him, and lifted him up. You little imp, how will you help us, they said. Listen, said he, I will creep into the pastor's room through the iron bars, and will reach out to you whatever you want to have. Come then, they said, and we will see what you can do. When they got to the pastor's house, thumbling crept into the room, but instantly cried out with all his might, do you want to have everything that is here. The thieves were alarmed, and said, but do speak softly, so as not to waken any one. Thumbling however, behaved as if he had not understood this, and cried again, what do you want. Do you want to have everything that is here. The cook, who slept in the next room, heard this and sat up in bed, and listened. The thieves, however, had in their fright run some distance away, but at last they took courage, and thought, the little rascal wants to mock us. They came back and whispered to him, come be serious, and reach something out to us. Then thumbling again cried as loudly as he could, I really will give you everything, just put your hands in. The maid who was listening, heard this quite distinctly, and jumped out of bed and rushed to the door. The thieves took flight, and ran as if the wild huntsman were behind them, but as the maid could not see anything, she went to strike a light. When she came to the place with it, thumbling, unperceived, betook himself to the granary, and the maid after she had examined every corner and found nothing, lay down in her bed again, and believed that, after all, she had only been dreaming with open eyes and ears. | Als Daumesdick merkte, daß sie fort waren, kroch er aus dem unterirdischen Gang wieder hervor. "Es ist auf dem Acker in der Finsternis so gefährlich gehen," sprach er, "wie leicht bricht einer Hals und Bein." Zum Glück stieß er an ein leeres Schneckenhaus. "Gottlob," sagte er, "da kann ich die Nacht sicher zubringen," und setzte sich hinein. Nicht lang, als er eben einschlafen wollte, so hörte er zwei Männer vorübergehen, davon sprach der eine "wie wirs nur anfangen, um dem reichen Pfarrer sein Geld und sein Silber zu holen?, "Das könnt ich dir sagen," rief Daumesdick dazwischen. "Was war das?" sprach der eine Dieb erschrocken, "ich hörte jemand sprechen." Sie blieben stehen und horchten, da sprach Daumesdick wieder "nehmt mich mit, so will ich euch helfen." "Wo bist du denn?" "Sucht nur auf der Erde und merkt, wo die Stimme herkommt," antwortete er. Da fanden ihn endlich die Diebe und hoben ihn in die Höhe. "Du kleiner Wicht, was willst du uns helfen!" sprachen sie. "Seht," antwortete er, "ich krieche zwischen den Eisenstäben in die Kammer des Pfarrers und reiche euch heraus, was ihr haben wollt." "Wohlan," sagten sie, "wir wollen sehen, was du kannst." Als sie bei dem Pfarrhaus kamen, kroch Daumesdick in die Kammer, schrie aber gleich aus Leibeskräften "wollt ihr alles haben, was hier ist?, Die Diebe erschraken und sagten "so sprich doch leise, damit niemand aufwacht." Aber Daumesdick tat, als hätte er sie nicht verstanden, und schrie von neuem "was wollt ihr? wollt ihr alles haben, was hier ist?" Das hörte die Köchin, die in der Stube daran schlief, richtete sich im Bete auf und horchte. Die Diebe aber waren vor Schrecken ein Stück Wegs zurückgelaufen, endlich faßten sie wieder Mut und dachten "der kleine Kerl will uns necken." Sie kamen zurück und flüsterten ihm zu "nun mach Ernst und reich uns etwas heraus." Da schrie Daumesdick noch einmal, so laut er konnte "ich will euch ja alles geben, reicht nur die H ände herein." Das hörte die horchende Magd ganz deutlich, sprang aus dem Bett und stolperte zur Tür herein. Die Diebe liefen fort und rannten, als wäre der wilde Jäger hinter ihnen; die Magd aber, als sie nichts bemerken konnte, ging ein Licht anzünden. Wie sie damit herbeikam, machte sich Daumesdick, ohne daß er gesehen wurde, hinaus in die Scheune: die Magd aber, nachdem sie alle Winkel durchgesucht und nichts gefunden hatte, legte sich endlich wieder zu Bett und glaubte, sie hätte mit offenen Augen und Ohren doch nur geträumt. |

|

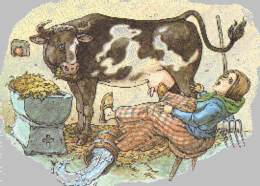

Thumbling had climbed up among the hay and found a beautiful place to sleep in. There he intended to rest until day, and then go home again to his parents. But there were other things in store for him. Truly, there is much worry and affliction in this world. When the day dawned, the maid arose from her bed to feed the cows. Her first walk was into the barn, where she laid hold of an armful of hay, and precisely that very one in which poor thumbling was lying asleep. He, however, was sleeping so soundly that he was aware of nothing, and did not awake until he was in the mouth of the cow, who had picked him up with the hay. Ah, heavens, cried he, how have I got into this mill. But he soon discovered where he was. Then he had to take care not to let himself go between the teeth and be dismembered, but he was subsequently forced to slip down into the stomach with the hay. In this little room the windows are forgotten, said he, and no sun shines in, neither will a candle be brought. His quarters were especially unpleasing to him, and the worst was that more and more hay was always coming in by the door, and the space grew less and less. When at length in his anguish, he cried as loud as he could, bring me no more fodder, bring me no more fodder. The maid was just milking the cow, and when she heard some one speaking, and saw no one, and perceived that it was the same voice that she had heard in the night, she was so terrified that she slipped off her stool, and spilt the milk. She ran in great haste to her master, and said, oh heavens, pastor, the cow has been speaking. You are mad, replied the pastor, but he went himself to the byre to see what was there. Hardly, however had he set his foot inside when thumbling again cried, bring me no more fodder, bring me no more fodder. Then the pastor himself was alarmed, and thought that an evil spirit had gone into the cow, and ordered her to be killed. She was killed, but the stomach, in which thumbling was, was thrown on the dunghill. Thumbling had great difficulty in working his way out. However, he succeeded so far as to get some room, but just as he was going to thrust his head out, a new misfortune occurred. A hungry wolf ran thither, and swallowed the whole stomach at one gulp. Thumbling did not lose courage. Perhaps, thought he, the wolf will listen to what I have got to say. And he called to him from out of his belly, dear wolf, I know of a magnificent feast for you. Where is it to be had, said the wolf. In such and such a house. You must creep into it through the kitchen-sink, and will find cakes, and bacon, and sausages, and as much of them as you can eat. And he described to him exactly his father's house. |

Daumesdick war in den Heuhälmchen herumgeklettert und hatte einen schönen Platz zum Schlafen gefunden: da wollte er sich ausruhen, bis es Tag wäre, und dann zu seinen Eltern wieder heimgehen. Aber er mußte andere Dinge erfahren! ja, es gibt viel Trübsal und Not auf der Welt! Die Magd stieg, als der Tag graute, schon aus dem Bett, um das Vieh zu füttern. Ihr erster Gang war in die Scheune, wo sie einen Arm voll Heu packte, und gerade dasjenige, worin der arme Daumesdick. lag und schlief. Er schlief aber so fest, daß er nichts gewahr ward, und nicht eher aufwachte, als bis er in dem Maul der Kuh war, die ihn mit dem Heu aufgerafft hatte. "Ach Gott," rief er, "wie bin ich in die Walkmühle geraten!, merkte aber bald, wo er war. Da hieß es aufpassen, daß er nicht zwischen die Zähne kam und zermalmt ward, und hernach mußte er doch mit in den Magen hinabrutschen. "In dem Stübchen sind die Fenster vergessen," sprach er, "und scheint keine Sonne hinein: ein Licht wird auch nicht gebracht." Überhaupt gefiel ihm das Quartier schlecht, und was das Schlimmste war, es kam immer mehr neues Heu zur Türe hinein, und der Platz ward immer enger. Da rief er endlich in der Angst, so laut er konnte, "bringt mir kein frisch Futter mehr, bringt mir kein frisch Futter mehr." Die Magd melkte gerade die Kuh, und als sie sprechen hörte, ohne jemand zu sehen, und es dieselbe Stimme war, die sie auch in der Nacht gehört hatte, erschrak sie so, daß sie von ihrem Stühlchen herabglitschte und die Milch verschüttete. Sie lief in der größten Hast zu ihrem Herrn und rief "ach Gott, Herr Pfarrer, die Kuh hat geredet." "Du bist verrückt," antwortete der Pfarrer, ging aber doch selbst in den Stall und wollte nachsehen, was es da gäbe. Kaum aber hatte er den Fuß hineingesetzt, so rief Daumesdick aufs neue "bringt mir kein frisch Futter mehr, bringt mir kein frisch Futter mehr." Da erschrak der Pfarrer selbst, meinte, es wäre ein böser Geist in die Kuh gefahren, und hieß sie töten. Sie ward geschlachtet, der Magen aber, worin Daumesdick steckte, auf den Mist geworfen. Daumesdick hatte große Mühe, sich hindurchzuarbeiten, und hatte große Mühe damit, doch brachte ers so weit, daß er Platz bekam, aber als er eben sein Haupt herausstrecken wollte, kam ein neues Unglück. Ein hungriger Wolf lief heran und verschlang den ganzen Magen mit einem Schluck. Daumnesdick verlor den Mut nicht, "vielleicht," dachte er, "läßt der Wolf mit sich reden," und rief ihm aus dem Wanste zu "lieber Wolf" ich weiß dir einen herrlichen Fraß." "Wo ist der zu holen?" sprach der Wolf. "In dem und dem Haus, da mußt du durch die Gosse hineinkriechen, und wirst Kuchen, Speck und Wurst finden, so viel du essen willst," und beschrieb ihm genau seines Vaters Haus. |

|

The wolf did not require to be told this twice, squeezed himself in at night through the sink, and ate to his heart's content in the larder. When he had eaten his fill, he wanted to go out again, but he had become so big that he could not go out by the same way. Thumbling had reckoned on this, and now began to make a violent noise in the wolf's body, and raged and screamed as loudly as he could. Will you be quiet, said the wolf, you will waken up the people. What do I care, replied the little fellow, you have eaten your fill, and I will make merry likewise. And began once more to scream with all his strength. At last his father and mother were aroused by it, and ran to the room and looked in through the opening in the door. When they saw that a wolf was inside, they ran away, and the husband fetched his axe, and the wife the scythe. |

Der Wolf ließ sich das nicht zweimal sagen, drängte sich in der Nacht zur Gosse hinein und fraß in der Vorratskammer nach Herzenslust. Als er sich gesättigt hatte" wollte er wieder fort, aber er war so dick geworden" daß er denselben Weg nicht wieder hinaus konnte. Darauf hatte Daumesdick gerechnet und fing nun an" in dem Leib des Wolfes einen gewaltigen Lärmen zu machen, tobte und schrie, was er konnte. "Willst du stille sein," sprach der Wolf, "du weckst die Leute auf." "Ei was," antwortete der Kleine, "du hast dich satt gefressen, ich will mich auch lustig machen," und fing von neuem an, aus allen Kräften zu schreien. Davon erwachte endlich sein Vater und seine Mutter, liefen an die Kammer und schauten durch die Spalte hinein. Wie sie sahen, daß ein Wolf darin hauste, liefen sie davon, und der Mann holte eine Axt, und die Frau die Sense. |

|

Stay behind, said the man, when they entered the room. When I have given the blow, if he is not killed by it, you must cut him down and hew his body to pieces. Then thumbling heard his parents, voices and cried, dear father, I am here, I am in the wolf's body. Said the father, full of joy, thank God, our dear child has found us again. And bade the woman take away her scythe, that thumbling might not be hurt with it. After that he raised his arm, and struck the wolf such a blow on his head that he fell down dead, and then they got knives and scissors and cut his body open and drew the little fellow forth. |

"Bleib dahinten," sprach der Mann, als sie in die Kammer traten, "wenn ich ihm einen Schlag gegeben habe, und er davon noch nicht tot ist, so mußt du auf ihn einhauen, und ihm den Leib zerschneiden." Da hörte Daumesdick die Stimme se ines Vaters und rief "lieber Vater, ich bin hier, ich stecke im Leibe des Wolfs." Sprach der Vater voll Freuden "gottlob, unser liebes Kind hat sich wiedergefunden," und hieß die Frau die Sense wegtun, damit Daumesdick nicht beschädigt würde. Danach holte er aus, und schlug dem Wolf einen Schlag auf den Kopf, daß er tot niederstürzte, dann suchten sie Messer und Schere, schnitten ihm den Leib auf und zogen den Kleinen wieder hervor. |

| Ah, said the father, what sorrow we have gone through for your sake. Yes father, I have gone about the world a great deal. Thank heaven, I breathe fresh air again. Where have you been, then. Ah, father, I have been in a mouse's hole, in a cow's belly, and then in a wolf's paunch. Now I will stay with you. And we will not sell you again, no not for all the riches in the world, said his parents, and they embraced and kissed their dear thumbling. They gave him to eat and to drink, and had some new clothes made for him, for his own had been spoiled on his journey. | "Ach," sprach der Vater, "was haben wir für Sorge um dich ausgestanden!, "Ja, Vater, ich bin viel in der Welt herumgekommen; gottlob, daß ich wieder frische Luft schöpfe!" "Wo bist du denn all gewesen?" "Ach, Vater, ich war in einem Mauseloch, in einer Kuh Bauch und in eines Wolfes Wanst: nun bleib ich bei euch." "Und wir verkaufen dich um alle Reichtümer der Welt nicht wieder," sprachen die Eltern, herzten und küßten ihren lieben Daumesdick. Sie gaben ihm zu essen und trinken, und ließen ihm neue Kleider machen, denn die seinigen waren ihm auf der Reise verdorben. |

<< Previous Page Next Page >>

© 2004-2007 Northvegr.

Most of the material on this site is in the public domain. However, many people have worked very hard to bring these texts to you so if you do use the work, we would appreciate it if you could give credit to both the Northvegr site and to the individuals who worked to bring you these texts. A small number of texts are copyrighted and cannot be used without the author's permission. Any text that is copyrighted will have a clear notation of such on the main index page for that text. Inquiries can be sent to info@northvegr.org. Northvegr™ and the Northvegr symbol are trademarks and service marks of the Northvegr Foundation.

|