[294]

THE NORSEMEN IN AMERICA.

BY RASMUS B. ANDERSON, LL. D.

CHAPTER I.

NORUMBEGA.

THE early discovery of this country by the Norsemen is of interest to every American. It is the first coming of Europeans to this continent. It is the first chapter of civilization in the Western world. It is also the first chapter of the history of the Christian Church in America; for Leif Erikson and his followers had been converted to Christianity and Leif was himself a missionary sent out by the king of Norway to preach the gospel of the Gallilean to the Norse colonists in Greenland.

Before the landing of the Pilgrims at Plymouth Rock in 1620, the shores of North America had been visited by the so-called French voyageurs. Some of these explorers wrote accounts of their voyages, and in their narratives and on maps which they published there is frequent mention of the name Norumbega. The name is found with a variety of spellings, Norumbegue, Norumbergue, sometimes with the initial "n" omitted, Anorabegra, Anorumbega, etc. It is applied to a country, river and city located somewhere in the eastern part of the United States or Canada. It is said to have been discovered by Verrazzano, in 1524. The site of the city [295] was given on a map published at Antwerp in 1570. In 1604 Champlain ascended the Penobscot River in Maine, supposing that stream to be the Norumbega. But after going twenty-two leagues he discovered no indications of a city or of civilization except an old moss-grown cross in the woods. American historians have found much difficulty in identifying Norumbega, The fact is the statements of the various French authorities are conflicting. As stated, the first mention is by Verrazzano on his map published in Antwerp in 1524, and later, that is, in 1539, Parmentier found the name Norumbega, applied to a country lying southwest from, Cape Breton. Allefonsce, under Roberval, in 1543, determined the fact of there being two Cape Bretons, of which the more southern, referred to by Parmentier, was in the forty-third degree and identical with Cape Anne. Within the limit of this forty-third degree was a river, at the mouth of which, according to Allefonsce, were many rocks and islands; up which river, as Allefonsce estimated, fifteen leagues from the mouth was a city called Norumbegue. "There was," Allefonsce said, "a fine people at the city and they had furs of many animals and wore mantles of martin skins." Allefonsce was a pilot by profession and on him particularly rests the identity of one of the Cape Bretons which Cape Anne and the fact of there being a river with a city on its banks, both bearing the name Norumbega between Cape Anne and Cape Cod. Wytfliet, in 1597, in an augment to Ptolemy, says, "Norombega, a beautiful city and a grand river, are well-known." He gives on his map a picture of the settlement, or villa, [297] at the junction of two streams, one of which is called the Rio Grande. Thevet in his texts places Fort Norumbegue at the point where Wytfliet placed the city, that is, at the junction of two streams, and Thevet says "To the north of Virginia is Norumbega, which is well-known as a beautiful city and a great river. Still one can not find whence this name is derived, for the natives call it Agguncia. At the entrance of the river there is an island very convenient for the fishery." Thevet describes the fort as surrounded by fresh water and at the junction of two streams. The city of Norumbega on his map is lower down the river. The French, who occupied the fort, called the fort Norumbega. As stated, the identification of Norumbega has greatly puzzled American historians, and the country, river and city have from, time to time been located at various points from Virginia to the St. Lawrence. Most authorities have referred Norumbega to New England, while Lok, in 1582, seems to have believed that the Penobscot in Maine formed its southern boundary. Before 1880 this view seems to have been very generally adopted by American scholars. Our poet, J. G. Whittier, made Norumbega the subject of one of his most beautiful poems.

In connection with the poem, the poet gives the following explanatory note, which well represents the concensus of opinion of American scholars before 1880: "Norembega, or Norimbegue, is the name given by early French fishermen and explorers to a fabulous country south of Cape Breton, first discovered by Verazzano in 1524. It was supposed to have a magnificent city of the [298] same name on a great river, probably the Penobscot. The site of this barbaric city is laid down cm a map published at Antwerp in 1570. In 1604, Champlain sailed in search of the Northern Eldorado, twenty-two leagues up the Penobscot from the Isle Haute. He supposed the river to be that of Norembega, but wisely came to the conclusion that those travelers who told of the great city had never seen it. He saw no evidence of anything like civilization, but mentions the finding- of a cross, very old and mossy, in the woods."

In 1881 Arthur James Weise, of Troy, N. Y., published a work called "The Discovery of America to the Year 1525." In the closing pages of this work he takes up the subject of Norumbega, and arrives at the conclusion that the name is a contraction of the old French L'Anormeeberge (the grand scarp), and claims that the adjective "anormee" and the noun "berge" definitely describe the wall of rocks known as the Palisades, on the Hudson river, above New York city. Weise has no doubt that by the term Norumbega river the Hudson is meant, and that the country around the Palisades was called by the French explorers La Terre d'Anormeeberge, afterwards contracted and corrupted into Norumbega and its other variations heretofore named. In identifying the river called by one of the French writers Norombega, with the present Hudson, Weise lays great stress upon the statement by the same writer that the water of the river was salty to the height of forty leagues, and shows that the Hudson is brackish beyond the city of Poughkeepsie. According to Weise, the city of Norumbega

|

[299]

must have occupied the site of the present Albany, the capital of New York. Weise's arguments seemed so conclusive, particularly his interpretation of the name, that his view was very generally accepted by students of American history everywhere.

Passing on to the year 1890, we come to an entirely new theory. Before presenting this in detail it may interest my readers to learn a few facts leading up. to it. In 1873 I suggested to the famous Norwegian violinist, Ole Bull, that Leif Erikson, the first white man who planted his feet on American soil, ought to be honored with a monument. Ole Bull accepted the suggestion with the greatest enthusiasm, and he and I together immediately prepared plans for its realization. During the spring of 1873 we arranged a number of entertainments in Wisconsin and Iowa, the proceeds of which made the nucleus of the Leif Erikson monument fund. At these entertainments Ole Bull played the violin and the writer sandwiched in short addresses to the audiences while the artist rested. Later, that same year, I accompanied Ole Bull to Norway, and there a series of entertainments were arranged for the same purpose. At one of these entertainments the distinguished Norwegian poet, Bjornstjerne Bjornson, delivered an address. A sum of money was realized from the entertainments in Norway for the monument fund. A few years later Ole Bull made his American home in Cambridge, Mass.; there he was successful in organizing a committee for the purpose of carrying out our plans in regard to the Leif Erikson monument. The committee was a most brilliant one. [300]

In it were found James Russell Lowell, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Oliver Wendell Holmes, Thomas S. Appleton, Prof. E. N. Horsford, the Governor of Massachusetts, the Mayor of Boston and many other distinguished people. Funds were rapidly raised, and America's most distinguished sculptress, Miss Anne Whitney (126), was engaged to produce in bronze a statue of Leif Erikson in heroic size. In due time the statue was completed and placed at the end of Commonwealth Avenue in Boston. The statue represents Leif Erickson as he discovers the first faint outlines of land far away on the horizon, and with his right hand he shades his eyes from the dazzling rays of the sun. The statue does not represent my idea of a long bearded and shaggy haired Norseman of the tenth century. Miss Whitney has made Leif smooth faced, with the general outlines of the Roman. She seems to have taken the splendid physique and features of Ole Bull for her model. But it is certainly a great work of art. No less authority than James Russell Lowell declared it to be the finest work of sculpture hitherto produced in America. A perfect replica, cast in the same mold as the original, was presented by a Milwaukee lady to the city of Milwaukee, where it can be seen by my readers. It stands on the lake front, a little north of the Chicago & Northwestern railway station, near the well-known Juneau monument.

It will be observed that Prof. Horsford was mentioned as one of the committee in Cambridge. Prof. Eben Norton [301] Horsford, born July 27th, 1818, was the son of a distinguished missionary among the Indians. The son, Eben., acquired from his father, who was thoroughly familiar with many Indian dialects, an extensive knowledge of Indian words. He studied science both in America and in Europe under Prof. Liebig, and became Professor of Science in Harvard University in 1847, a position which he filled with distinction for sixteen years. Fortune smiled on him. He became wealthy and was able to devote his time exclusively to scientific and literary pursuits. He was a large hearted man and gave generously of his wealth to educational institutions. Wellesley College is under great obligations to him.

The organization of the Leif Erickson committee in Cambridge attracted his attention to the subject of the Norse discovery of America. The result was that he practically abandoned his other studies and concentrated all his energies on investigations bearing on the Norse voyages to this country. He was particularly interested in locating the landfall of Leif Erikson and in identifying the country explored by him and his countrymen from the tenth to the fourteenth century. Some idea can be formed of Prof. Horsford's enthusiasm in this cause when we learn that he spent more than $50,000 in making explorations, in publishing books and maps, and in building monuments and memorials in honor of the Norse discoverer. He was the orator at the unveiling of the Leif Erikson monument in Boston.

In 1890, Prof. Horsford presented an entirely new theory in regard to the perplexing question of Norumbega. [302]

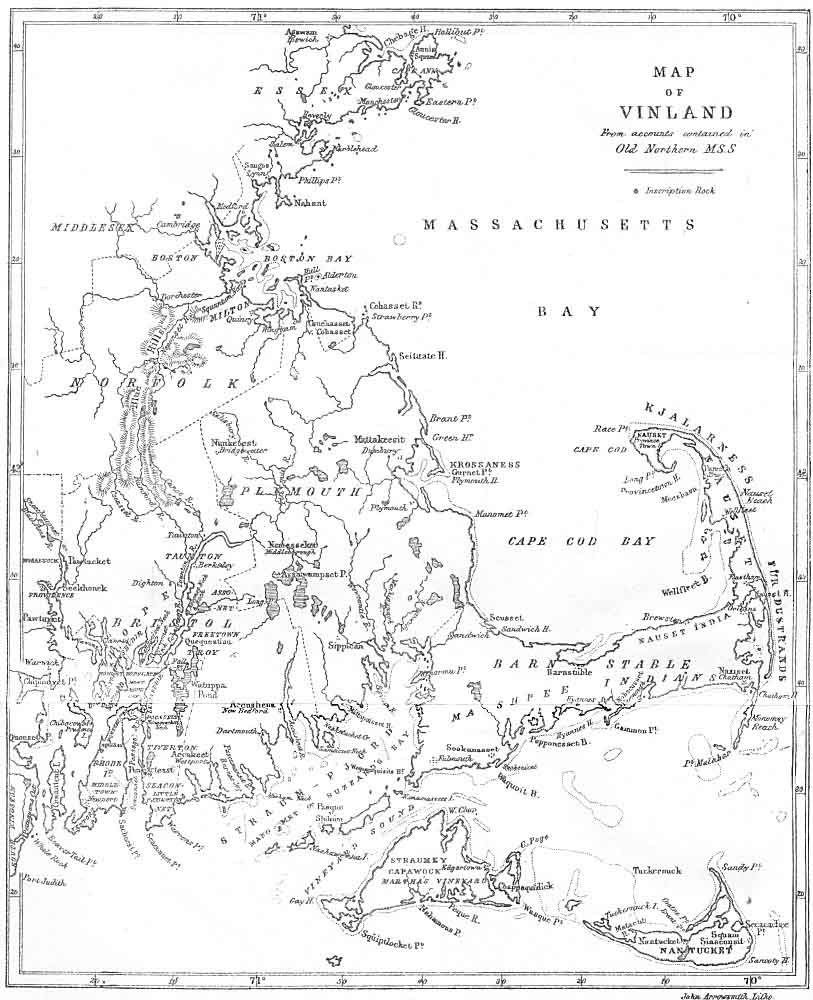

In this year appeared his "Discovery of the Ancient City of Norumbega." In it he claims to have found the precise site of the ancient city, and locates it with absolute confidence on the Charles river, in Massachusetts, at its junction with Stony Brook, near Walton. He makes Norumbega identical with the Vinland of the Norseman, claiming that Norumbega is not derived from the old French D'Anormee Berge, but is a corruption of the old name Norvegr and that it has borne that name among the aborigines ever since the Norse explorers in the tenth and following centuries made their headquarters there. He takes Norumbega to be the name the French voyageurs did not bestow but found. So thoroughly convinced was Prof. Horsford of the correctness of his theory that he built on the site which he identified as Norumbega a costly tower in commemoration of the Norse discoverers and colonists. Prof. Horsford found at and around the junction of Stony Brook with Charles river evidences of a great industry involving, among other things, a graded area some four acres in extent, paved with field boulders. At the base of the bluffs along Stony Brook there are ditches or canals extending far into the country and above the ditches are walls made of boulders from three to five feet high. The existence of these works has long been known, but their origin has never been satisfactorily interpreted. It is certain that they existed before the landing of the Pilgrim Fathers in 1620. It is equally certain that they are the handiwork of man. They are too extensive to have been produced by the French or English explorers previous [303] to 1620. They can scarcely be ascribed to the aborigines, for they differ widely from any works known to have been constructed by the natives of this country. The old Norse sagas tell us that the Norseman carried timber from Vinland to Greenland and Prof. Horsford suggests that the canals were filled with water at high tide and that logs were floated down to where their ships lay in the Charles river. He supposes that the walls above the canals were constructed to protect the canals from being filled with debris from the bluffs. When the immediate shores of the river had been cleared of wood the shores of the tributaries flowing into the river became the field of activity and maple blocks were sent floating down the stream; and where the streams were remote from the bases of the slopes on either side the sources of water were at hand. Canals, or nearly level troughs, were dug to transport the logs to the streams and ultimately to the Charles. Dams and ponds were necessary at the mouths of the streams to prevent the blocks from going down the Charles without a convoy and out to sea to be lost. There is an admirable canal, walled on one side, extending for a thousand feet along the western bank of Stony Brook in the woods above the Tiverton railroad crossing, between Walton and Weston. The Cheesecake Brook is another and Cold Spring Brook another, and there is an interesting dry canal near Murray Street, not far from Newtonville. It may be seen from the railroad cars on the right, a little to the east of Eddy Street, approaching Boston. Prof. Horsford found throughout the basin of the Charles numerous [304] canals, ditches, deltas, boom-dams, ponds, fish-ways, forts, dwellings, walls, terraces of theatre and amphitheatre, and he insisted that there was not a square mile drained into the Charles River that lacked an incontestable monument of the presence of the Norsemen. I have myself gone over the most of this ground in company with Prof. Horsford and listened to his enthusiastic interpretations of these strange remains. It may seem as an undeserved dignity to speak of these ditches as canals, but they are so named in the old deeds in Weston, and if you look at them on the left of the highway, between Sibley's and Weston, with the stone wall on either side, you will not wonder that the word canal, as well as ditch, should have suggested itself. They are so called on the published town maps of Millis and Holliston. Prof. Horsford, as indicated, bought a tract of land at the junction of Stony Brook with Charles River, consecrating it to the memory of the Norsemen, and set up in Weston, at the mouth of Stony Brook, a magnificent tower. Over the tablet, set in the wall of the tower, is poised the Icelandic falcon about to alight with a new world in his talons. On the tablet is given the following inscription:

A. D. 1000, A. D. 1889.

NORUMBEGA.

City--Country--Fort--River.

Norumbega--Nor'mbega.

Indian utterance of Norbega, the Ancient Form of Norvega,

Norway, to which the Region of

Vinland was Subject.

Notes:

(126) Miss Anne Whitney was born in Watertown, Mass. She opened a studio as sculptress in Boston in 1873, and has made among other notable works, a statue of Samuel Adams and one of Harriet Martineau. [Back]

© 2004-2007 Northvegr.

Most of the material on this site is in the public domain. However, many people have worked very hard to bring these texts to you so if you do use the work, we would appreciate it if you could give credit to both the Northvegr site and to the individuals who worked to bring you these texts. A small number of texts are copyrighted and cannot be used without the author's permission. Any text that is copyrighted will have a clear notation of such on the main index page for that text. Inquiries can be sent to info@northvegr.org. Northvegr™ and the Northvegr symbol are trademarks and service marks of the Northvegr Foundation.

|