[162]

SECOND PERIOD.

WE have thus seen how the desire to tell of old times arose and was propagated amongst the inhabitants of the new colony. But the remembrance and relation of individual exploits, and the transmission of these records from one generation to the other, would perhaps have never led to the Icelanders becoming historians had not such habits been united with a strong feeling for poetry, a desire for fame, and that peculiar state of society which had been formed amongst them.

The Island had been colonized in peace; each enterprising navigator as he touched its shore took possession of a tract of land without impediment, and became the independent proprietor of his small estate; but now these settlements approached each other; interests began to clash; individual demeanour to become developed. The social bonds had been too loosely attached to keep within due limits the wild self will of so many impetuous Northmen. True, their ancient Norwegian customs had been spontaneously resumed on their arrival, and fifty years later (A. D. 928), the laws of Ulfliot had given a form and consistency to the moral code; but these checks had little weight when individual power or interest were enabled to oppose them. Personal strength was necessary for personal safety; and the many narratives which have been preserved, detailing the untimely fate of the most respectable families in the course of the first two centuries, exhibit a long list of feuds and deeds of violence unchecked by the laws or the judicial authority of the land. [163]

These civil broils were not, however, in general, of a very sanguinary character, and often consisted of individual encounters, where courage and presence of mind were equally exhibited on both sides, and the contest was obstinate: in a more general fray the loss was looked upon as considerable if ten men fell.

The time of feud was also a time of re-union: the object of the individual was spread abroad; discussion was created, sympathy was awakened; the relative merits of the contending parties became the theme of conversation, and the Skalds were stimulated to the composition of new specimens of their inspiring art. On particular occasions they improvised. Hate as well as love formed the theme of these effusions, and the same means were employed to give a graceful form to satire, in which style of composition these ancient poets were remarkably successful: in fact, so cutting were these sallies, and of so much weight among a people peculiarly under the influence of public opinion, that they often became the causes of bloodshed, and were looked upon as a ground of complaint before the Courts (79). For the most part, however, the songs were of an historical character; sometimes the Skald sang of his own exploits, sometimes of those of his friends, who upon such occasions were accustomed to present him with costly gifts: After the Norwegian Skald, Eyvind Skialdespilder, had sung a Drapa or ode in praise of the Icelanders, every peasant in the island contributed three pieces of silver, which were applied to the purchase of a clasp or ornament for a mantel [164] that weighed 50 marks and this they sent to the bard, as an acknowledgment of his poetic powers.

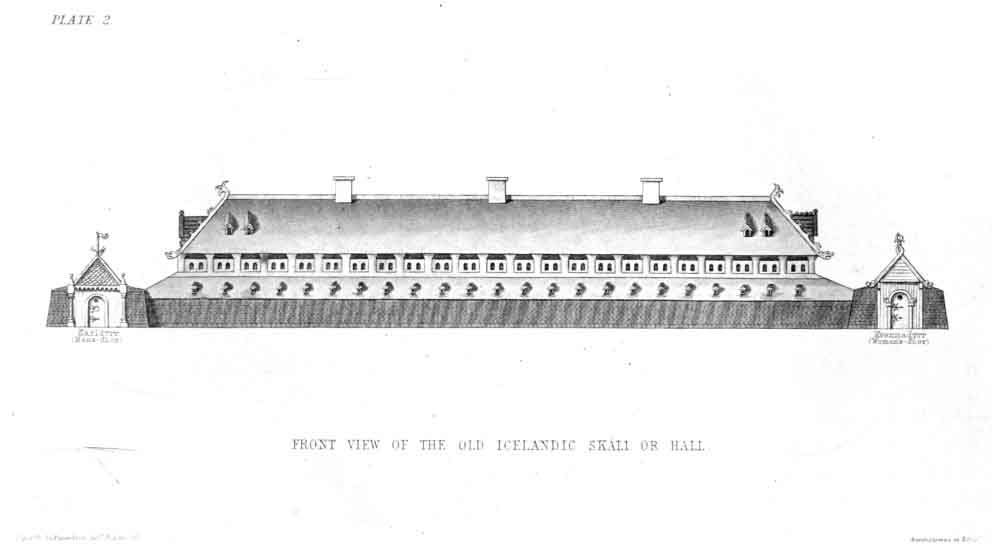

The climate and mode of living contributed to keep alive this taste for poetry, which the Icelanders had inherited from their Norwegian ancestors. Agriculture was almost entirely confined to the care of pasture and meadow land; fishing could only be carried on at certain seasons, and the feeding of cattle required little attention. Their hostile proceedings were also soon concluded; but was a reprisal apprehended, it became necessary for the chief to retain his followers at the farm until a reconciliation was brought about, and these assemblages in the common room, during the long winter evenings, contributed to increase the social union and reciprocal communication of past events. Public amusements also brought the people frequently together: besides the great feasts, which lasted from eight to fourteen days, sports and games, such as bowls or wrestling, were carried on in the several districts for many weeks in succession; and still more attractive was the Heste-thing, where stallions were made to fight against each other, to the great amusement of both old and young. To these reunions must be added those caused by attendance at the different courts, and particularly at the Althing (80) or general Assizes, where all the first men of the island met annually, with great pomp and parade. It was looked upon as a disgrace to be absent from this meeting, which was held in the open air on the banks of the Thingvalla Vatn, the largest lake in Iceland, a natural hill or mount forming the court.

To figure here with a display and retinue that drew upon him the eyes of all beholders, was the great ambition of the [165] Chief, whose power and influence depended much upon the number of friends and followers he could produce on such occasions. These were again determined by the degree of support and assistance which they could calculate on obtaining from him in the hour of need; and hence the anxiety on the part of the Icelandic yeoman to be fully acquainted with the character and circumstances of his chief, to which cause may be more immediately attributed the interest which he took in all new Sagas or narratives of remarkable individuals.

In the Laxdæla Saga (81) it is related that, after a brave Icelander, named Bolle Bolleson, had gallantly defeated an assailant, by whom he had been attacked in the course of a journey through the island, his exploit became the subject of a new Saga, which quickly spread over the district and added considerably to his reputation. In Gisle Sursens Saga, a stranger is introduced, saying to his neighbours at the court--"Shew me the men of great deeds, those from whom the Sagas proceed."

The greater number of the remaining Sagas bear what may be called a political stamp; they contain a detail of the most important disputes between individual families, or districts, painted in the most minute manner, and followed by a general description of the most important personages in the narrative. How much weight was attached to these personal descriptions is shewn by the nature of the Icelandic language, which is richer than any other European tongue in words that express those various qualities and shades of character which are of the most importance in society. The exterior of the chief person in the Saga is [166] also painted with equal accuracy, especially his features, in which the richness of the language is also observable; and even the particulars of the dress are not omitted. This was of importance in a country where it was not always easy to determine whether the stranger who made his appearance was friend or foe, and a remarkable instance is mentioned in the Laxdæla Saga of a chief named Helge Hardbeinsen identifying some stranger knights, whom he had never seen, solely from the accurate description of their personal appearance, which was brought to him by the messenger who communicated the intelligence of their approach.

The same characteristics are imprinted on the Sagas. The peculiarities of the narrator never appear; it is as if one only heard the simple echo of an old tradition; no introductory remarks are made, but the history begins at once abruptly with:--"There was a man called so and so, son of so and so," etc.: no judgment is pronounced upon the transaction, but it is merely added that this deed increased the hero's reputation, or that was considered bad. In most Sagas the dialogistic form prevails, particularly in those of more ancient date, for this form was natural to the people, who insensibly threw their narratives into dialogue, and thus they acquired a more poetical colouring; for not only were the conversations related which had actually taken place, but also those which from the nature of the subject it might have been concluded had been held; and the general mode of expression being simple and nearly uniform, and the character being best developed in this definite form, those imaginary conversations were, for the most part, not inconsistent with truth.

The talent for narrating was naturally generated by the desire of hearing these narratives. Those Skalds who remembered [167] the old Sagas, and whose imagination was lively, were best enabled to adopt the dramatic form, and now, independent of their local or political interest, the narratives became interesting on their own account. Scarce a century after the colonization of the country we find that the people took great pleasure in this amusement. "Is no one come," asks Thorvard, at a meeting of the people mentioned in Viga Glums Saga, "who can amuse us with a new story?" They answered him: "There is always sport and amusement when thou are present." He replied: "I can think of nothing better than Glum's songs," upon which he sang one of those which he had learned. In the Sturlunga Saga a certain priest, named Ingemund, is mentioned as a man rich in knowledge, who told good stories, afforded much amusement, and indited good songs for which he obtained payment abroad. Such a narrator was called a Sagaman.

Thus did oral tradition, beginning with the mythic, proceed thence to the historical and end with the fabulous. We have now come to the period when books were written and collected in the island; but in order to trace the cause of that peculiar fondness for their own history, which led the Icelanders not only to become the historians of Iceland but of the whole North, it is necessary to go back to the earlier condition of the country and the people.

It may at first sight appear that the local position of this remote island would be alone sufficient to prevent the inhabitants from taking any interest in the affairs of other countries; but the communication with Norway continued; the migration from thence lasted for many generations, even after the island was colonized, and many merchant ships passed annually between Iceland and the parent state. They brought with them meal, building-timber, leather, fine [168] cloth and tapestry, taking in exchange silver, skins, coarse cloth (Wadmel), and other kinds of wollens, as well as dried fish.

As soon as it was known that a merchant had brought a cargo to the Icelandic coast the chief of the temple, and in later times the governor of the province, rode down immediately to the ship and asked for news; he then fixed the price at which the various goods were to be sold to the people of the district, chose what he wanted for himself, and invited the captain of the vessel to stop at his house for the winter. The visitor was now looked upon as one of the family, he entered into their amusements, and disputes, entertained them at Yule with his stories, and presented his host at parting with a piece of English tapestry, or some other costly gift, in return for the hospitality which he had received. Piratical expeditions had at this time given place to trading voyages, and the merchant or ship's captain was often a person of good family sometimes attached to the Norwegian Court, and hence well acquainted with ail that was passing there. How much this intercourse tended to the increase of historical material is shown by an old MS. of St. Olafs Saga, wherein is stated that:--"In the time of Harald Haarfager there was much sailing from Norway to Iceland; every summer was news communicated between the two countries, and this was afterwards remembered, and became the subject of narratives."

The Icelanders not only received intelligence from Norway, but brought it away themselves. They were led to undertake these voyages as well from the desire to see their relations, and claim inheritances, as for the purpose of procuring more valuable building-timber than the merchant could bring them. The chief considered that his reputation

|

Notes:

(79) "As an instance of the effect produced by these satirical songs, it is related that Harold Blaatand, King of Denmark, was so incensed at some severe lines which the Icelanders had made upon him for seizing one of their ships, that he sent a fleet to ravage the island, which occurrence led them to make a law subjecting any one to capital punishment who should indulge in satire against the Sovereigns of Norway, Sweden and Denmark!" [Back]

(80) Ting or Thing signifies in the old Scandinavian tongue to speak, and hence a popular assembly, or court of justice. The national assembly of Norway still retains the name of Stor-thing, or great meeting, and is divided into two chambers called the Lag-thing, and Odels-thing. [Back]

(81) The annals of a particular family, as the Eyrbiggia Saga is of a particular district in Iceland. The former has been translated into Latin by Mr. Repp, and Sir Waiter Scott has given a brief account of the other. [Back]

© 2004-2007 Northvegr.

Most of the material on this site is in the public domain. However, many people have worked very hard to bring these texts to you so if you do use the work, we would appreciate it if you could give credit to both the Northvegr site and to the individuals who worked to bring you these texts. A small number of texts are copyrighted and cannot be used without the author's permission. Any text that is copyrighted will have a clear notation of such on the main index page for that text. Inquiries can be sent to info@northvegr.org. Northvegr™ and the Northvegr symbol are trademarks and service marks of the Northvegr Foundation.

|