[92] his promises to Gudrid. He sold his lands and live-stock in the spring, and accompanied Gudrid to the ship, with all his possessions. He put the ship in order, procured a crew, and then sailed to Ericsfirth. The bodies of the dead were now buried at the church, and Gudrid then went home to Leif at Brattahlid, while Thorstein the Swarthy made a home for himself on Ericsfirth, and remained there as long as he lived, and was looked upon as a very superior man.

OF THE WINELAND VOYAGES OF THORFINN AND HIS COMPANIONS.

That same summer a ship came from Norway to Greenland. The skipper's name was Thorfinn Karlsefni; he was a son of Thord Horsehead, and a grandson of Snorri, the son of Thord of Hofdi. Thorfin Karlsefni, who was a very wealthy man, passed the winter at Brattahlid with Leif Ericsson. He very soon set his heart upon Gudrid, and sought her hand in marriage; she referred him to Leif for her answer, and was subsequently betrothed to him, and their marriage was celebrated that same winter. A renewed discussion arose concerning a Wineland voyage, and the folk urged Karselfni to make the venture, Gudrid joining with the others. He determined to undertake the voyage, and assembled a company of sixty men and five women, and entered into an agreement with his shipmates that they should each share equally in all the spoils of the enterprise. They took with them all kinds of cattle, as it was their intention to settle the country, if they could. Karlsefni asked Leif for the

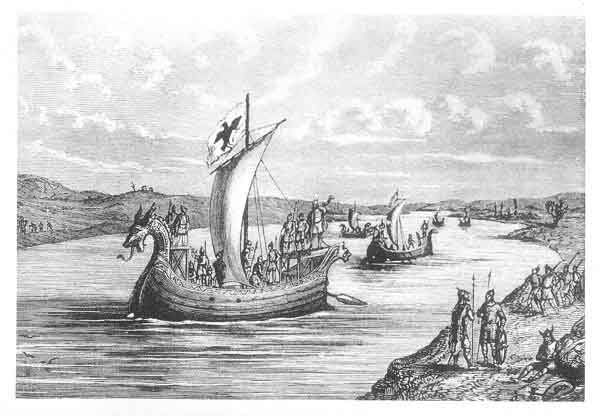

IT appears most probable from the text that when Karlsefni sailed from Iceland to visit the New World, in about the year 1003, his expedition comprised more than two ships. The saga mentions two ships, and also relates that on one ship were forty men. Considering that there was a total of 160 men in the company, while the character of the vessels used scarcely allowed for provisions and accommodation, for more than fifty men each, it is almost certain that three or more ships were included in the expedition. That the vessels were small or of very light draft is proved by their ability to navigate in rivers. as related in the saga. From the nature of the country described it is believed that the stream ascended was the Charles River that issues near Boston. |

[93] house in Wineland, and he replied, that he would lend it but not give it. They sailed out to sea with the ship, and arrived safe and sound at Leifs-booths, and carried their hammocks ashore there. They were soon provided with an abundant and goodly supply of food, for a whale of good size and quality was driven ashore there, and they secured it, and flensed it, and had then no lack of provisions. The cattle were turned out upon the land, and the males soon became very restless and vicious; they had brought a bull with them. Karlsefni caused trees to be felled, and to be hewed into timbers, wherewith to load his ship, and the wood was placed upon a cliff to dry. They gathered somewhat of all of the valuable products of the land, grapes, and all kinds of game and fish, and other good things. In the summer succeeding the first winter, Skrellings were discovered. A great troop of men came forth from out the woods. The cattle were hard by, and the bull began to bellow and roar with a great noise, whereat the Skrellings were frightened, and ran away, with their packs wherein were grey furs, sables and all kinds of peltries. They fled towards Karlsefni's dwelling, and sought to effect an entrance into the house, but Karselfni caused the doors to be defended [against them]. Neither [people] could understand the other's language. The Skrellings put down their bundles then, and loosed them, and offered their wares [for barter], and were especially anxious to exchange these for weapons, but Karlsefni forbade his men to sell their weapons, and taking counsel with himself, he bade the women carry out milk to the Skrellings, which they no [94] sooner saw than they wanted to buy it, and nothing else. Now the outcome of the Skrelling's trading was, that they carried their wares away in their stomachs, while they left their packs and peltries behind with Karlsefni and his companions, and having accomplished this [exchange] they went away. Now it is to be told that Karlsefni caused a strong wooden palisade to be constructed and set up around the house. It was at this time that Gudrid, Karlsefni's wife, gave birth to a male child, and the boy was called Snorri. In the early part of the second winter the Skrellings came to them again, and these were now much more numerous than before, and brought with them the same wares as at first. Then said Karlsefni to the women: "Do ye carry out now the same food, which proved so profitable before, and nought else." When they saw this they cast their packs in over the palisade. Gudrid was sitting within, in the doorway, beside the cradle of her infant son, Snorri when a shadow fell upon the door, and a woman in a black namkirtle (70) entered. She was short in stature, and wore a fillet about her head; her hair was of a light chestnut colour, and she was pale of hue, and so big-eyed that never before had eyes so large been seen in a human skull. She went up to where Gudrid was seated, and said: "What is thy name?" "My name is Gudrid; but what is thy name?" "My name is Gudrid," says she. The housewife, Gudrid, motioned her with her hand to a seat beside her; but it so happened, that at that very instant Gudrid heard a great crash, whereupon the woman vanished, and at that same moment one of the Skrellings, [95] who had tried to seize their weapons, was killed by one of Karlsefni's followers. At this the Skrellings fled precipitately, leaving their garments and wares behind them; and not a soul, save Gudrid alone, beheld this woman. "Now we must needs take counsel together," says Karlsefni, "for that I believe they will visit us a third time, in great numbers, and attack us. Let us now adopt this plan: ten of our number shall go out upon the cape, and show themselves there, while the remainder of our company shall go into the woods and hew a clearing for our cattle, when the troop approaches from the forest. We will also take our bull, and let him go in advance of us." The lay of the land was such that the proposed meeting-place had the lake upon the one side and the forest upon the other. Karlsefni's advice was now carried into execution. The Skrellings advanced to the spot which Karlsefni had selected for the encounter, and a battle was fought there, in which great numbers of the band of the Skrellings were slain. There was one man among the Skrellings, of large size and fine bearing, whom Karlsefni concluded must be their chief. One of the Skrellings picked up an axe, and having looked at it for a time, he brandished it about one of his companions, and hewed at him, and on the instant the man fell dead. Thereupon the big man seized the axe and after examining it for a moment he hurled it as far as he could, out into the sea; then they fled helter-skelter into the woods, and thus their intercourse came to an end. Karlsefni and his party remained there throughout the winter, but in the spring Karlsefni announced that he was not minded [96] to remain there longer, but would return to Greenland. They now made ready for the voyage, and carried away with them much booty in vines and grapes and peltries. They sailed out upon the high seas, and brought their ship safely to Ericsfirth, where they remained during the winter.

FREYDIS CAUSES THE BROTHERS TO BE PUT TO DEATH

There was now much talk anew, about a Wineland-voyage, for this was reckoned both a profitable and an honourable enterprise. The same summer that Karlsefni arrived from Wineland, a ship from Norway arrived in Greenland. This ship was commanded by two brothers, Helgi and Finnbogi, who passed the winter in Greenland. They were descended from an Icelandic family of the East-firths. It is now to be added that Freydis, Eric's daughter, set out from her home at Gardar, and waited upon the brothers, Helgi and Finnbogi, and invited them to sail with their vessel to Wineland, and to share with her equally all of the good things which they might succeed in obtaining there. To this they agreed, and she departed thence to visit her brother, Leif, and ask him to give her the house which he had caused to be erected in Wineland, but he made her the same answer [as that which he had given Karlsefni], saying that he would lend the house, but not give it. It was stipulated between Karlsefni and Freydis, that each should have on ship-board thirty able-bodied men, besides the women; but Freydis immediately violated this compact, by concealing five men more [than this number], and this the [97] brothers did not discover before they arrived in Wineland. They now put out to sea, having agreed beforehand that they would sail in company, if possible, and although they were not far apart from each other, the brothers arrived somewhat in advance, and carried their belongings up to Leif's house. Now when Freydis arrived, her ship was discharged, and the baggage carried up to the house, whereupon Freydis exclaimed: "Why did you carry your baggage in here?" "Since we believed," said they, "that all promises made to us would be kept." "It was to me that Leif loaned the house," says she, "and not to you." Whereupon Helgi exclaimed: "We brothers cannot hope to rival thee in wrong-dealing." They thereupon carried their baggage forth, and built a hut, above the sea, on the bank of the lake, and put all in order about it; while Freydis caused wood to be felled, with which to load her ship. The winter now set in, and the brothers suggested that they should amuse themselves by playing games. This they did for a time, until the folk began to disagree, when dissensions arose between them, and the games came to an end, and the visits between the houses ceased; and thus it continued far into the winter. One morning early, Freydis arose from her bed, and dressed herself, but did not put on her shoes and stockings. A heavy dew had fallen, and she took her husband's cloak, and wrapped it about her, and then walked to the brothers' house, and up to the door, which had been only partly closed by one of the men, who had gone out a short time before. She pushed the door open, and stood silently in the doorway for a [98] time. Finnbogi, who was lying on the innermost side of the room, was awake, and said: "What dost thou wish here, Freydis?" She answers: "I wish thee to rise, and go out with me, for I would speak with thee." He did so, and they walked to a tree, which lay close by the wall of the house, and seated themselves upon it. "How art thou pleased here?" says she. He answered: "I am well pleased with the fruitfulness of the land, but I am ill-content with the breach which has come between us, for, methinks, there has been no cause for it." "It is even as thou sayest," said she, "and so it seems to me; but my errand to thee is, that I wish to exchange ships with you brothers, for that ye have a larger ship than I, and I wish to depart from here." "To this I must accede," said he, "if it is thy pleasure." Therewith they parted, and she returned home, and Finnbogi to his bed. She climbed up into bed, and awakened Thorvard with her cold feet, and he asked her why she was so cold and wet. She answered, with great passion: "I have been to the brothers," said she, "to try to buy their ship, for I wish to have a larger vessel, but they received my overtures so ill, that they struck me, and handled me very roughly; what time thou, poor wretch, will neither avenge my shame nor thy own, and I find, perforce, that I am no longer in Greenland; moreover I shall part from thee unless thou wreakest vengeance for this." And now he could stand her taunts no longer, and ordered the men to rise at once, and take their weapons, and this thy did, and they then proceeded directly to the house of the brothers, and entered it while the folk were asleep, and [99] seized and bound them, and led each one out when he was bound; and as they came out, Freydis caused each one to be slain. In this wise all of the men were put to death, and only the women were left, and these no one would kill. At this Freydis exclaimed: "Hand me an axe!" This was done, and she fell upon the five women, and left them dead. They returned home, after this dreadful deed, and it was very evident that Freydis was well content with her work. She addressed her companions, saying: "If it be ordained for us to come again to Greenland, I shall contrive the death of any man who shall speak of these events. We must give it out that we left them living here when we came away." Early in the spring they equipped the ship, which had belonged to the brothers and freighted it with all of the products of the land, which they could obtain, and which the ship would carry. Then they put out to sea, and after a prosperous voyage arrived with their ship, in Ericsfirth early in the summer. Karlsefni was there, with his ship all ready to sail, and was awaiting a fair wind; and people say that a ship richer laden than that which he commanded never left Greenland.

CONCERNING FREYDIS.

Freydis now went to her home, since it had remained unharmed during her absence. She bestowed liberal gifts upon all of her companions, for she was anxious to screen her guilt. She now established herself at her home; but her companions were not all so close-mouthed, concerning their misdeeds and wickedness, that rumours did not [100] get abroad at last. These finally reached her brother, Leif, and he thought it a most shameful story. He thereupon took three of the men, who had been of Freydis' party, and forced them all at the same time to a confession of the affair, and their stories entirely agreed. "I have no heart," says Leif, "to punish my sister, Freydis, as she deserves, but this I predict of them, that there is little prosperity in store for their offspring." Hence it came to pass that no one from that time forward thought them worthy of aught but evil. It now remains to take up the story from the time when Karlsefni made his ship ready, and sailed out to sea. He had a successful voyage, and arrived in Norway safe and sound. He remained there during the winter, and sold his wares, and both he and his wife were received with great favour by the most distinguished men of Norway. The following spring he put his ship in order for the voyage to Iceland; and when all his preparations had been made, and his ship was lying at the wharf, awaiting favourable winds, there came to him a Southerner, a native of Bremen in the Saxonland, who wished to buy his "house-neat." "I do not wish to sell it," said he. "I will give the half a 'mork' in gold for it" (71), says the Southerner. This Karlsefni thought a good offer, and accordingly closed the bargain. The Southerner went his way, with the "house-neat," and Karlsefni knew not what it was, but it was "mosur," come from Wineland.

Karlsefni sailed away, and arrived with his ship in the north of Iceland, in Skagafirth. His vessel was beached there during the winter, and in the spring he bought [101] Glaumbœiar-land, and made his home there, and dwelt there as long as he lived, and was a man of the greatest prominence. Prom him and his wife, Gudrid, a numerous and goodly lineage is descended. After Karlsefni's death, Gudrid, together with her son, Snorri, who was born in Wineland, took charge of the farmstead; and when Snorri was married Gudrid went abroad and made a pilgrimage to the South, after which she returned again to the home of her son, Snorri, who had caused a church to be built at Glaumbœr. Gudrid then took the veil and became an anchorite, and lived there the rest of her days. Snorri had a son, named Thorgeir, who was the father of Ingveld, the mother of Bishop Brand. Hallfrid was the name of the daughter of Snorri, Karlsefni's son; she was the mother of Runolf, Bishop Thorlak's father. Biorn was the name of [another] son of Karlsefni and Gudrid; he was the father of Thorunn, the mother of Bishop Biorn. Many men are descended from Karlsefni, and he has been blessed with a numerous and famous posterity; and of all men Karlsefni has given the most exact accounts of all these voyages, of which something has now been recounted.

Notes:

70) Námkrytill [namkirtle] is thus explained by Dr. Valtýr Gudmundsson, in his unpublished treatise on ancient Icelandic dress: "Different writers are not agreed upon the meaning of 'námkrytill;'" Sveinbjörn Egilsson interprets it as signifying a kirtle made from some kind of material called "nám." In this definition he is followed by Keyser. The Icelandic painter, Sigurdr Gudmundsson has, on the other hand, regarded the word as allied to the expression: "Fitting close to the leg, narrow," [147] and concludes that "námkyrtill" should be translated, "narrow kirtle." [Back]

(71) A "Mark" was equal to eight "aurar;" an "eyrir" [plur. "aurar"] of silver was equal to 144 skillings. An "eyrir" would, therefore, have been equal to three crowns [kroner], modern Danish coinage, since sixteen skillings are equal to one-third of a crown [33 ? ore], and a half "mark" of silver would accordingly have been equal to twelve crowns, Danish coinage. As the relative value of gold and silver at the time described is not clearly established, it is not possible to determine accurately the value of the half "mark" of gold. It was, doubtless, greater at that time, proportionately, than the value here assigned, while the purchasing power of both precious metals was very much greater then than now. [Back]

© 2004-2007 Northvegr.

Most of the material on this site is in the public domain. However, many people have worked very hard to bring these texts to you so if you do use the work, we would appreciate it if you could give credit to both the Northvegr site and to the individuals who worked to bring you these texts. A small number of texts are copyrighted and cannot be used without the author's permission. Any text that is copyrighted will have a clear notation of such on the main index page for that text. Inquiries can be sent to info@northvegr.org. Northvegr™ and the Northvegr symbol are trademarks and service marks of the Northvegr Foundation.

|