Chapter 3

88

Ivar's realm, however, was probably a loosely knit confederacy of vassal states. Indeed, if it is correct to identify the Hogne and Granmar of the Helgi Lays in the elder Edda with the kings of the same name in the Ynglingasaga (p. 78), it might be argued that Ivar was rather the ally than the conqueror of the states of Östergötland and Södermanland. At his death, however, the confederacy, if such it was, collapsed, and confusion reigned until Ivar's grandson once more united the several states under a single direction. This new chieftain of eastern Scandinavia was Harald Hilditönn.

All the saga-sources agree that Harald won back by slow degrees his grandfather's vast kingdom, but though he lived to an old age he met his death in battle and as a result his possessions were seized by an upstart ruler. This was one of the great battles of early Scandinavian history, a contest that was long remembered by the scalds and chroniclers. It was fought at Bravalla, probably close to Norrköping in Östergötland, about the middle of the eighth century, and the issue of the battle affected very considerably the distribution of the balance of power in Scandinavia. The difficulty, however, is that while modern scholars do not deny the historicity of the battle, (1) the personality and nationality of the protagonists is by no means easy to decide. There has, indeed, been a wide divergence from the saga-traditions in the attempts to square the accounts of the battle with the supposed political condition of the time. It is, however, little short of perverse to claim that Harald Hilditönn was anything other than king of "'Greater Denmark'", a ruler of Denmark and Scania whose sway extended by right of conquest over a very large area of Sweden, even perhaps over Svitjod itself. Many of these districts within his kingdom were ruled by sub-kings who had sworn allegiance to Harald, and his adversary at Bravalla, Sigurd Hring, must assuredly have been one of these sub-kings risen in rebellion against him. But who was this Sigurd Hring? The Hervararsaga, which is of thirteenth-century date, declares that he was a nephew of Harald and a sub-king in Denmark itself. (2) The Sögubrot, written about 1300, agrees that Hring was a nephew

1. See, for instance, A. Olrik, Namn och Bygd, 1914, p. 297; A. Nordén, Saga och sägen i Bråbygden, 1922, pp. 28-52; and Östergötlands Järnålder, 1929, I, 196; E. Hjärne, Namn och Bygd, 1917, p. 56; T. Hederström, Fornsagor och Eddakväden, I, 1917, pp. 20-60; B. Nerman, Det sve nska rikets uppkomst, p. 253.

2. Ed. S. Bugge, 1864, p. 292.

89

of Harald, but says that Harald had made him king of Svitjod and Västergötland. (1) Saxo Grammaticus, writing about 1200, also makes Hring to be Harald's nephew (but by his sister, not his brother) and describes him as king of Sweden. (2) The slightly earlier Leire Chronicle (late twelfth century) is another source in which Hring is described as king of Sweden, (3) but there is one saga, that of Herrand and Bose which was written in the fourteenth century, that depicts Hring, who is not said in this account to be a close relative of Harald, as the ruler of Östergötland.

Without entering into a full argument as to the exact situation of Sigurd Hring's country, it seems to be a safe inference from the united testimony of these sources that the great Bravalla battle represented the secession from the Danish confederacy of one or more of the northern states that had submitted to Ivar Vidfadmi and to Harald Hilditönn. The long accounts of the battle, and the description of the vast hosts and mighty heroes alleged to have taken part in it, are sufficient to show that it was fought to decide great issues and that its result must have been a turning-point in Scandinavian history. Harald met his death, the Danish supremacy came to an abrupt end, and once more the states of central Sweden, Västergötland, Östergötland, and Svitjod, now perhaps coalesced under the rule of Sigurd Hring, were free to shape their own destiny, to increase and to prosper until at length they stood before the world as the united kingdom of Sweden. It would be doubtless a serious overstatement to declare that the immediate sequel to Bravalla was the foundation of the modern Swedish state, for the gain to Svitjod from this victory cannot accurately be assessed. But at least it is certain that in the next century the Danes held only the extreme south of Sweden in addition to their own territories, and that the old distinction between Swedes and Goths as peoples of separate kingdoms had disappeared, the names Swedes and Sweden henceforward embracing the Goths and Götaland. (4)

1. Ed. C. Petersen and E. Olson, Samfund t. udgivelse af gammel nordisk litt., XLVI, p. 15.

2. VII, 367 (ed. Müller).

3. Cap. IX, P. 53 (ed. Gertz, SS. Min. Hist. Dan., 1917).

4. The fact that the missionary Anskar, who preached in Sweden, refers only to the Swedes and the Swedish kingdom, seems to be proof of this, for Anskar had a detailed knowledge of Scandinavian affairs. It is true that the travellers and missionaries who supply our meagre information about Scandinavia in the ninth and tenth centuries all seemed to have approached Sweden by its eastern Baltic coast, so that

90

It is an unfortunate thing for the purpose of the present narrative that the formation of the state of Sweden in the dark centuries following upon the battle of Bravalla should be an event that is lost to history; but there is no escape from this conclusion inasmuch as the paucity of records after the battle makes any conjecture as to the full story a rash and unprofitable enterprise. It must be sufficient to say that from the end of the eighth century onwards there may have been a single kingdom of Sweden possessing, except for some territories in the extreme south and west, almost the whole of the lands of modern Sweden.

The time has come, then, to turn once more to the story of early Denmark, though, first, a preliminary word must be said concerning affairs on the Continent.

The long and bitter struggle between the Saxons and the Franks that had endured throughout the eighth century ended with the triumph of the now Christian and cultured Franks over their dour heathen adversaries. In 772 Charles the Great himself invaded the lands of the Saxons and destroyed that focus of their pagan worship, the Irmensul in its sacred grove, at the same time forcing the reluctant heathen to admit his missionaries. For twenty more years they resisted him still, but when Charles at length resorted to mass deportations the Saxon power was broken. Henceforward their revolts became less frequent and feebler until in the middle of the ninth century they had ceased.

The Danish lands, therefore, after Bravalla, were subject to a new influence, namely the advent near the Danish frontier of the Franks themselves. It was a circumstance of no little importance. This was no contact with mere brother Germans, rough heathens of the same calibre as the Danes themselves or their familiar neighbours the Saxons and Frisians. The Franks, on the contrary, were a civilized and instructed people, inheritors of a rich legacy of Roman culture and determined evangelists of the Christian faith. Their relations with the people of Denmark could not fail, therefore, to bring upon the uncouth Danes all the disturbing consequences, both social and political, that

91

so often follow the throwing together of a rich and powerful people, intent upon spreading the gospel of their own religion, with a humbler folk. Of this clash between the Danes and the Franks something may be learnt from the Frankish chronicles. (1)

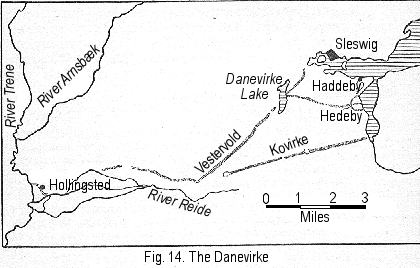

The history of the Danes as derived from these sources opens with the flight of the Saxon chief Widukind in 777 to Denmark; there he took refuge with a Danish king called Sigfred who subsequently entered into diplomatic relations with Charles the Great. At the beginning of the ninth century Sigfred had been succeeded by Godfred, a very powerful king. (2) He collected an army to oppose Charles, being fearful perhaps of the loss of his revenues as a result of the appearance of the Franks upon the Frisia-Baltic trade-route, and in 808 he overthrew the emperor's allies, the Obotrits, a Slavonic people living in the modern Mecklenberg region, and built a defensive dyke extending half-way across the country from the Baltic coast near Sleswig to the Hollingstedt swamps, this being the renowned Danevirke (3) (Fig. 14). Two years

1. Chief of these for ninth-century Denmark are the Annales Einhardi (Pertz, M.G.H., SS. I, pp. 157, 191 ff.), Annales Fuldenses (ib. p. 354 ff.), and Annales Bertiani (ib. p. 424 ff.).

2. This was the Godfred identified by N. M. Petersen, P. A. Munch, and G. Storm with the Vestfold (Norwegian) king Gudröd (see p. 106) who is mentioned in the Ynglingatal; see Storm Kritiske Bidrag til Vikingetidens Historie, Oslo, 1878, p. 34 ff. The case for a partial conquest of Denmark at this period cannot, however, be seriously maintained; indeed, the identification was abandoned by Storm himself, Arkiv f. nordisk Filologi, XV (1898), 133-5. This matter of Godfred's supposed Yngling ancestry must not nevertheless be allowed to prejudice the question of the subsequent existence of a Dano-Norwegian kingdom.

3. There is a large literature dealing with the Danevirke. The principal authoritative account is that by S. Müller and C. Neergaard, Fortidsminder, I (1903), but it is important to consult Vilh. La Cour Danevirke, Copenhagen, 1917, and Geschichte des schleswigschen Volkes, I, Flensburg, 1923, and other recent descriptions such as that by Hans Kjaer , Vor Oldtids Mindesmaerker, Copenhagen, 1925, p. 177 ff.; cf. furthermore, the references to papers by S. Lindqvist and E. Wadstein (p. 97). Godfred Danevirke consists of the Vestervold and the Ostervold, though this last has now almost completely disappeared. The earthwork was 8 1/2 miles long, and in its best preserved portion is now over 60 feet broad and 9 feet in height; it has no ditch. The port of Hedeby was situated on the coast of Hedeby Nor 2 miles to the east of the Danevirke; it was enclosed by a semicircular dyke shutting off an area of 54 acres and connected with the main Danevirke by a dyke without a ditch. South of Hedeby and running westwards to the southern bulge of the Danevirke is another fortification, the Kurvirke or Kograv, a dyke 3 3/4 miles long with a ditch on its south side; this is obviously a forward extension of the frontier protecting Hedeby. It is supposed that the connecting dyke between Hedeby and the Danevirke proper was built by Harald Gormsson (late ninth century), but the date of the Kurvirke is uncertain. It is probably a late structure, although E. Wadstein regards it as the original Godfred's dyke. The Vestervold itself is complicated by the addition of a massive stone revetment, popularly attributed to Thyra, king Gorm's queen (mid ninth century), and, later, by an additional frontal wall constructed by Valdemar the Great (twelfth century).

92

later he is said to have operated with his fleet against the Frisian coasts. His relative (nepos) Hemming succeeded him, and for the time being a peace was established between the Franks and the Danes. In 812, following upon the death of Hemming, there was a long struggle for the throne between Godfred's descendants and those of an earlier king called Harald. After fortune had favoured both sides with temporary success the crown passed eventually to one of Godfred's five sons, but Harald, a namesake and descendant of the earlier Harald, appealed to the emperor, now Charles's son Louis (814-840), for help. He was eventually reinstated as co-regent with one of Godfred's sons (or possibly allotted a portion of the Danish

realm), but, later on, he was once more expelled. This time he made certain of the lasting favour of Louis the Pious by adopting the Christian faith (826); but even this did not prevent his second expulsion from Denmark, and he then settled in some lands at the mouth of the Weser that he held in fief from the Frankish emperor (p. 196).

<< Previous Page Next Page >>

© 2004-2007 Northvegr.

Most of the material on this site is in the public domain. However, many people have worked very hard to bring these texts to you so if you do use the work, we would appreciate it if you could give credit to both the Northvegr site and to the individuals who worked to bring you these texts. A small number of texts are copyrighted and cannot be used without the author's permission. Any text that is copyrighted will have a clear notation of such on the main index page for that text. Inquiries can be sent to info@northvegr.org. Northvegr™ and the Northvegr symbol are trademarks and service marks of the Northvegr Foundation.

|