Introduction

Plate IV

(Opens New Window)

29

there appear such noble pieces as those carved by the great Oseberg artist whom Dr. Shetelig has called the Academist. But the feeling for classical simplicity and the inclusion of occasional geometrical and foliate forms did not seriously combat the northern love for animal forms, and the outcome was that the viking began to contrive patterns of half naturalistic human or leonine little creatures clutching hold of one another in a semi-plastic style of stumpy, solid forms that was quite unlike the purely linear design of Vendel art. Thus there arose the ninth-century viking style of the Gripping Beast that is illustrated here by the top of a box-brooch from the island of Gotland (Pl. II, 4) and that is a style of three phases; the first, Viking I (or Early Oseberg), is represented on the brooch, and then there is the succeeding Viking-Baroque (or Late Oseberg), and thirdly the Borre (1) phase which begins at the end of the ninth century and carries the gripping-beast style over into the tenth century, where it survives in elaborate and altered forms like the decoration on the oval brooch from Santon in Norfolk (Pl. II, 5). This 'gripping-beast' style, in so far as it reveals a new taste for substance and modelling in surface pattern, was probably a result of the influence of Carolingian and Byzantine wood-carving and sculpture, and the spirit of the new designs with its 'clutching' forms is quite plainly derived from the illuminated manuscripts, ivories, and metalwork of the English, the Irish, and the Franks.

But the experiment with the poor little gripping-beast forms had not satisfied the Scandinavian artist who was often unsuccessful in controlling and adapting the new motif. As the Oseberg and Gokstad ships show, some northern craftsmen still remained faithful to their old love, the linear animal, and were carving heads in profile and even drawing the linear animal itself throughout the period when the gripping beast was the fashion. Gradually the semi-plastic forms gave way before the revived profile animal, but by the end of the ninth century these designers were beginning to know something about Celtic art with its enchanting animal-drawings, and so when the profile creature began once more to be the main theme of the northern patterns, it was in an altered and Irish-looking form; thus late in the ninth century was born the splendid Jellinge Style (2) that was

1. Borre is in Vestfold, Norway, north of Oseberg. This art-convention (it is not really a distinct style) was named and defined by H. Shetelig, Osebergfundet, III, 295.

2. Jellinge is near Veile in Jutland, Denmark; it is the site of the royal barrows and runestones (Pl. VI) described on p. 100 . The typical and early 'Jellinge' animal-ornament is to be seen on a little silver cup from one of the great barrows.

30

to dominate viking art throughout the tenth century and to live on until the eleventh had well-nigh run its course.

The new Jellinge animal was contorted into the old tangle of limbs and body, but this time the northern artists did not occupy themselves exclusively with twisted writhing animals, for they also set themselves to work out new patterns of intertwining plant-scrolls, snakes, and ribbons, and in order to perfect these they borrowed many details from both eastern and western art. This gave them the opportunity of simplifying and emphasizing their beloved animal-theme, since the twists and twirls could now be introduced independently, and so by the end of the tenth century they had learnt to prefer a 'Great Beast', of the kind they had seen on Anglian monuments, that they drew according to their own spirited formula and surrounded by and enmeshed in the sprays and knots which represented, despite the foreign origin of the elements, the feeling for delicate and intricate patterns that was inherited from Vendel art. The Jellinge style in this 'Great Beast' phase that begins in the '70s or '80s of the tenth century is illustrated here (Pl. VI) by the renowned memorial stone at Jellinge set up by King Harald Gormsson.

Even in the eleventh century the Jellinge style, still with its 'great Beast', can be recognized in such lovely and fantastic things as the wood-carvings of about A.D. 1080 that adorn the outside and inside of the Urnes mast-church at the end of the Sogn fjord in Norway, and this beautiful 'Urnes' phase is represented here in miniature by a small ornament in openwork bronze from Norway (Pl. II, 3). This style is, however, matched and excelled in the contemporary Irish metalwork and there is no doubt that it owes as much to direct influence from Ireland as it does to the native Jellinge tradition.

In the first half of the century, however, in the days of King Cnut's Anglo-Danish kingdom and of the busy traffic across Russia with the Byzantine world and the Arabic east, the character of the now beloved foliate and ribbon ornament changes, and in the period A.D. 1000-1050 this is executed in what is known as the Ringerike Style. (1) The new convention seems to be most of all influenced by English design, but its graceful leaf-work is also to be found in symmetrical palmette-like patterns that are probably of oriental origin and that seem to have been so sufficient and satisfactory in the eyes of the

1. Ringerike is a district of the Buskerud province of Norway and lies immediately N.W. of Oslo and the Tyri fjord. A group of carved sandstone monuments here has given the style its name.

31

northern artists that they were now prepared to abandon their ancient animal-theme; yet in the beginning the new style was employed in designs of the Jellinge taste as background to the great beast and it is so displayed upon the well-known viking

grave-stone from St. Paul's Churchyard that is now in the Guildhall Museum in London. Moreover, Ringerike designs were often enriched by the addition of animal heads as terminals for the scrolls and tendrils, and this can be seen in the half-Jellinge carving of the St. Paul's

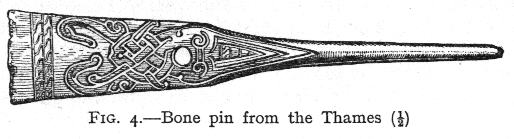

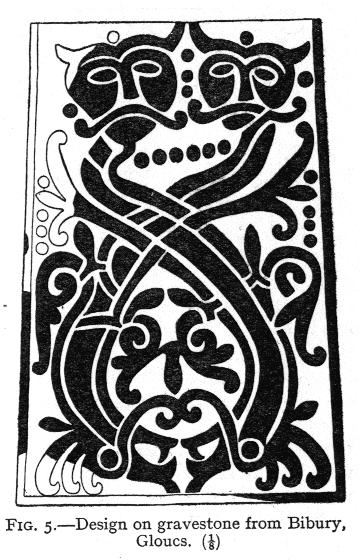

Churchyard slab or, as a reminder of Jellinge animal-art, in the lovely bronze panel, perhaps part of a viking weathervane, that is now preserved at Winchester. The Ringerike style, however, is really more notable because it represents a break with the old animal-tradition than because of its occasional blending with Jellinge animal-ornament; for it is as something new to northern art that it appears in the simple and solitary decoration of such small objects as the bone pin (Fig. 4) found in the Thames or in the more elaborate designs carved on the London gravestone now in the British Museum and on the Ringerike stones themselves; it is a departure from tradition, again, in such a piece of sculpture as the gravestone (Fig. 5) with the mask-terminals from Bibury, Gloucestershire; but the Ringerike style is perhaps best of all

32

exemplified as a new and virile art when it was adopted as the favourite formula of the clever Swedish designers who employed it so effectively upon their rune-stones and who so cunningly worked its patterns in silver on sword-hilts and the sockets of iron spear-heads. At the end of the Viking Period a new and mediaeval-looking animal appears in northern art, and though the old tradition was then vanishing and the conventions of the Middle Ages taking its place, yet this beast was sometimes drawn in a graceful, fiery Ringerike manner, as upon the gilt weather-

(Opens New Window)

vane (Fig. 6) from Hedden Church, Norway; this is probably a work of the late eleventh century and it shows how the spirit of viking art lived on to invigorate a continental mediaeval design.

So short a summary as this of the leading northern decorative styles does not by any means cover the whole field of viking art. In a fuller account something would have to be said of the Northman's feeling for colour, of the way whereby he used paints to heighten the effect of his carvings in wood and stone, and of the gay and vigorous painting, now only just recognizable, on the flat panels of the Oseberg chair, on the Jellinge woodwork,

33

and in the interior of the mast-churches. Likewise it would be necessary to speak of the attempts (sometimes rather clumsy) to carve upon the memorial stone figure-scenes of men and animals such as are to be found on some of the viking crosses in the Isle of Man. Worthy of mention too would be the much more successful carvings of the Northman's beloved and beautiful boat. One famous stone depicting a magnificent ship of the ninth century is reproduced here (Pl. IV). It comes from Stenkyrka in the island of Gotlandf and must be rated among the noblest monuments of the north; yet it is a piece of sculpture that is emphatically not the work of an artist bound by the conventions of the 'styles', but of a master-sculptor of a Swedish school that was intent upon the composition of balanced pictorial works according to its own stately tradition.

In spite of some aesthetic sensibility and a real cleverness in the designing of surface-ornaments, the Northman did not achieve any remarkable triumphs in such fields as that of architecture or sculpture in the round. Nevertheless his peculiar skill in the ship-yards had given him some encouragement to experiment in timber-architecture, and the few remaining mastchurches of early Norway such as that at Garmo near Lom and the better-known Urnes church, both of eleventh-century date, are witness to the grandeur of many a vanished hall of the Scandinavian kings and chieftains. But elaborate ornamental structures of that kind can scarcely be called typical homes of the viking folk, and the ordinary northern house was probably of a much simpler sort, timber-built as a rule in Scandinavia, but often made half of turf and stone, especially in the treeless countries of Iceland and Greenland. The furniture, which was usually carved in the homes of wealthy men, was wooden, and the rest of the household equipment simple in the extreme, consisting of pots and pans of iron and vessels of horn and wood; there were, however, plenty of iron tools, such as knives, sickles, scythes, and pincers, but in addition to these there were stone implements for the roughest work. Poor 'Burnt Njal' of Iceland, whose homestead at Bergthorshvoll has been excavated and whose pathetic and charred belongings can now be seen in the museum at Reykjavik, seems to have lived a life that cannot have been very much of an improvement upon that of neolithic man. He had iron tools, certainly, but his house contained a large assortment of perforated stone hammers of various sizes and a mass of grooved stone line-sinkers and stone door weights;

1. Dr. Thordarson tells me that many of these were probably fishsleggjur, fish-hammers, and were used for crushing dried cod-heads.

<< Previous Page Next Page >>

© 2004-2007 Northvegr.

Most of the material on this site is in the public domain. However, many people have worked very hard to bring these texts to you so if you do use the work, we would appreciate it if you could give credit to both the Northvegr site and to the individuals who worked to bring you these texts. A small number of texts are copyrighted and cannot be used without the author's permission. Any text that is copyrighted will have a clear notation of such on the main index page for that text. Inquiries can be sent to info@northvegr.org. Northvegr™ and the Northvegr symbol are trademarks and service marks of the Northvegr Foundation.

|